A regular analysis of strategy, decisions and calls that impacted the week of NFL play -- with help from ESPN senior analytics specialist Brian Burke among other resources.

Poets and songwriters have been saying it for centuries: Sometimes what you're looking for was right in front of you all along.

Take a look at the photograph below. At the top, you'll see NFL line judge Sarah Thomas approaching a pile of players after a fumble. Thomas is doing what officials are tasked to do in those situations: Find the football and determine possession.

On the left is Cleveland Browns running back Duke Johnson Jr. He's the guy who fumbled the ball with nine minutes, 41 seconds remaining in the game. Now he's raising it with his right hand for Thomas and the rest of the world to see.

Browns receiver Terrelle Pryor is the player walking off the field at the top. He already has seen Johnson with the ball and pointed in the Browns' direction. The player facing Johnson is offensive lineman Joel Bitonio, and you can see him noticing the ball as well.

So the Browns kept possession, right?

Well ...

Even as Johnson held the ball high above his head, Browns left tackle Joe Thomas and Washington Redskins linebacker Will Compton were wrestling at the bottom of the pile next to him. What they were wrestling for, or with, is anyone's guess.

Noticing their struggle, several other players dropped to the ground in search of the ball. Thomas focused her gaze toward the action and awarded Compton the ball as umpire Shawn Smith and back judge Steve Freeman approached.

There is no point on the broadcast video of the game when we see Compton with the ball, despite his earnest attempts in the pile to find it. Nor can we see any moment at which Thomas, Smith or Freeman looked at Johnson.

What in the world happened here? And why didn't the NFL's replay system, which reviews all fumbles awarded to the opposing team, fix it?

According to ESPN Cleveland Browns reporter Pat McManamon, Browns players heard Thomas tell the other officials that she saw a Redskins player with the ball and that Johnson grabbed it from him afterwards. To be fair, we've all seen that happen from time to time. Sometimes it fools officials, who are required by the NFL rule book to award possession to the first player who "secures possession of a loose ball after it has touched the ground" -- not the one who has the ball at the end of the action.

There is no evidence of that explanation on the game video. When you watch the full play at live speed, it sure looks like Johnson fumbled the ball, grabbed it himself and stood up with it in a matter of a second or two. The parallel universe that formed next to him was bizarre and yet not uncommon amid the chaos of an NFL game.

Replay is supposed to provide a safety net in these situations, but unfortunately for the Browns, there was no angle that showed a clear view of Johnson recovering the ball on the ground. An NFL spokesman told McManamon there was "nothing definitive" to see, and that's accurate. The league's standard for overturning calls on replay is that it's "clear and obvious" a mistake was made. There is a moment or two when we can't see the ball on the replay, allowing for the possibility that the on-field ruling was correct.

The play marked a significant turn in the game. The Redskins had just taken a 24-20 lead, and regaining possession raised their win probability from 63.6 percent to 86.5 percent in what would be a 31-20 victory.

Mistakes are made in every NFL game -- by officials, players and coaches alike. You can count on that continuing as long as humans are involved. In this case, however, we have a visual that accentuates it for posterity.

No pushing, Tartt!

The NFL is cracking down on taunting and unsportsmanlike conduct in a way we haven't seen in recent memory, a topic I'll write about later this week. (For now: Bows and arrows are bad. Cartwheels are good.) But one priority the league has never stopped enforcing is protection of the quarterback, as San Francisco 49ers safety Jaquiski Tartt found out Sunday.

Tartt was penalized 15 yards for unnecessary roughness after doing nothing more than pushing Dallas Cowboys quarterback Dak Prescott to the ground during a sack. When you watch the replay closely, you see and hear this succession of events:

Prescott remaining on his feet but no longer moving forward as 49ers pass-rushers Chris Davis and Ronald Blair wrap him up

Referee Terry McAulay raising his hand to end the play

A whistle

Tartt launching toward Prescott from behind and pushing him in the back with two hands.

Technically, the play was a violation of Rule 12, Section 2, Article 6 (d), which prohibits "running, diving into or throwing the body against or on a runner whose forward progress has been stopped."

But the preceding analysis is based on studying the play multiple times, in both slow motion and normal speed. In real time, everything essentially happened at once. Tartt followed his instinct to get a strong quarterback on the ground as he struggled to break free from his pursuers. It was aggressive, given the unlikelihood that Prescott was going to get away, but it's unlikely anyone would have protested had McAulay kept the flag in his pocket.

In the end, we were reminded that NFL referees are instructed to always, always, always err on the side of penalizing -- and thereby providing disincentives for -- borderline hits to the quarterback. And in this case, the penalty had massive ramifications on the game.

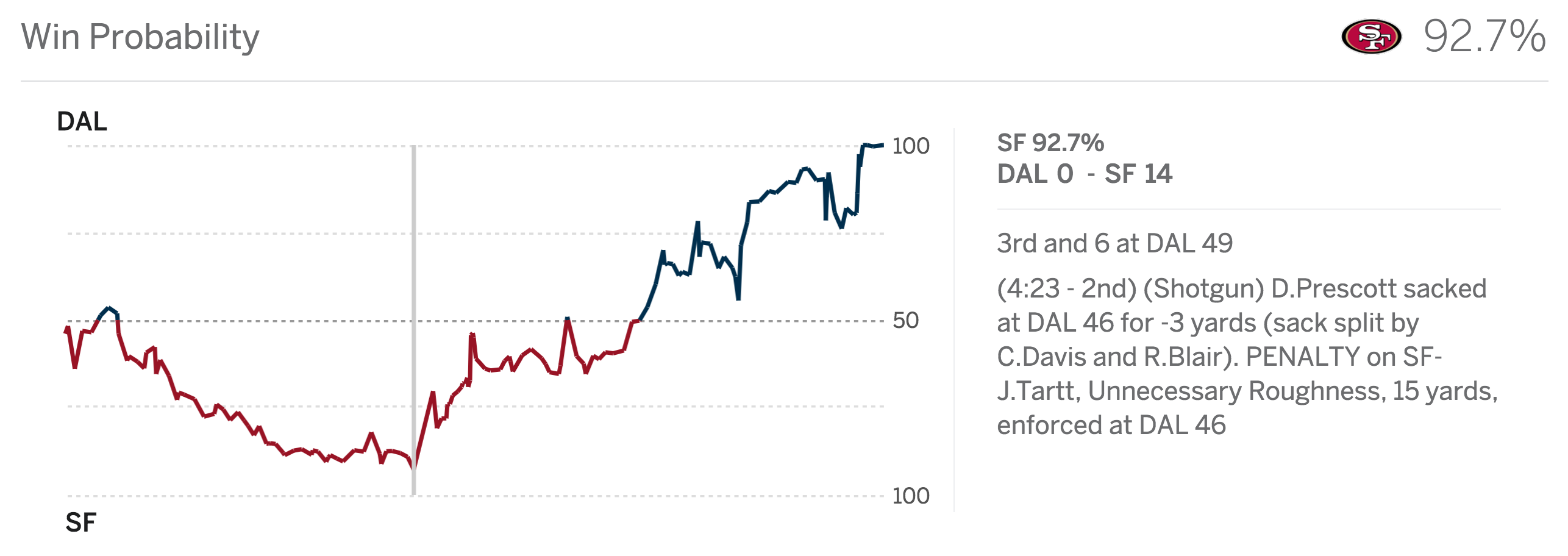

As you can see on the win probability graph, the 49ers' chances to win the game were never better than before the penalty. The Cowboys, trailing 14-0 at the time, received a first down at the 49ers' 39-yard line instead of facing fourth-and-9 from their 46. Three plays later, Dallas scored a touchdown and ultimately tallied 24 of the game's final 27 points in a 24-17 victory.

Two-point conversion rates settle in

Sunday night, Pittsburgh Steelers coach Mike Tomlin called for the NFL's first two-point conversion attempt in the first quarter of a game this season. The Steelers converted to take an early 8-0 lead over the Kansas City Chiefs, providing a reminder that the two-point play is a more attractive option than it once was now that the NFL has permanently moved extra point kick attempts to the 15-yard line.

Coaches this season are roughly mirroring their 2015 pace. As the chart shows, the conversion rate stands at 60 percent on 25 attempts, up from 52 percent on 29 attempts through four full weeks of the 2015 season.

Since the start of the 2015 season, teams are averaging a two-point attempt after 7.3 percent of their touchdowns, according to ESPN Stats & Information. That's up from 4.6 percent in 2014, the last year of spotting extra points at the 2-yard line.

Tomlin's Steelers are leading the way with a rate of 20.3 percent, but we're still not seeing the larger-scale transition toward two-point attempts that analytics suggest should be in order. The next-highest team is the Tennessee Titans (16.3 percent), who have been motivated more by deficits than aggressiveness. (They've lost 16 of 20 games since the rule was initiated.) Three teams -- the New England Patriots, New York Jets and Philadelphia Eagles -- have not attempted one in that span.

And even Tomlin appears to make the decision by feel more than odds. A penalty after the Steelers' second touchdown gave him the opportunity to try a two-point conversion from the 1-yard line rather than the 2, a decidedly favorable scenario. Instead, Tomlin opted to move the extra point 5 yards closer to the 10-yard line. Chris Boswell's 28-yard kick gave the Steelers a 15-0 lead en route to a 43-14 victory.

Accuracy on the longer extra point, meanwhile, seems to have settled between 94 and 95 percent. So coaches must decide whether to take the 95 percent odds that they'll get one point after a touchdown or the roughly 50 percent chance of getting two points. Most, not surprisingly, are opting for the better odds of fewer points.