Nathaniel S. Butler/Getty Images

Nathaniel S. Butler/Getty ImagesDavid Stern believes that small markets can't compete, but the truth is all around him.

If you followed NBA commissioner David Stern’s media tour last week, you probably heard him recite the following statement ad nauseum in one form or another:

The Lakers have a payroll of $110 million while the Sacramento Kings only have a payroll of $45 million. This is a real competitive balance issue that desperately needs fixing.

Stern is incredibly gifted when it comes to these things. He knows that the casual fan will look at those two figures and arrive at the tidy conclusion that the Kings simply cannot compete with the Lakers. I mean, look at that payroll disparity! Stern’s pitch is that the success of a team is directly tied to how much money they spend. And if you look at his example, how could you possibly disagree with him?

But then you look at the standings.

You notice that Stern did not sell the unfairness of payroll disparity by pitting the Orlando Magic against the Chicago Bulls. The Magic spent $110 million last season (the same as the Lakers) and the Bulls shelled out a lowly $55 million, or half as much as its Eastern conference foe. And the result? The poor Bulls won more games than any other team and reached the Eastern Conference Finals. The Magic? The nine-figure payroll bought them an embarrassing first-round exit.

If you scan through team payrolls, you begin to see that money doesn’t decide games. If cash was king, then the Bulls wouldn’t have a chance against the Magic. If spending power ruled all, how do we explain the Utah Jazz and their $80 million payroll winning 16 fewer games than the Oklahoma City Thunder, who spent just $58 million? The Toronto Raptors boasted a higher payroll than the Miami Heat, so why did the Raps lose 60 games while the Heat came within two games of a title?

The NBA has brought up the fact that the last four champions are big major market teams who spent a lot of money. While this is factually accurate, four consecutive years does not make a trend. Consider this: the previous five champions were smaller market teams (Spurs, Pistons and Heat). Evidently, the lesson changes as you slide the endpoints to make your argument. If we look over the past decade, the tally marks for titles between big market teams and small markets teams are equal at five.

The NBA is a complicated place, but when you cut through the rhetoric and look at the track record of the league, this much is clear: payroll doesn’t matter nearly as much it seems.

It’s about the draft, not dollars

Want to win games? Win the draft first. There you’ll find the breeding ground for championship teams. Dirk Nowitzki was drafted by the Mavericks (in a draft-day trade). Tim Duncan was drafted by the Spurs. Kobe Bryant was drafted by the Lakers (in a draft-day trade). Michael Jordan was drafted by the Bulls. Dwyane Wade and the Heat, Hakeem and the Rockets, so on and so forth.

There are some rare exceptions (e.g. the 2004 Pistons), but if you flip through through the title winners every season, you’ll find that the championship blueprint usually begins with hitting a home run on draft night.

To see why this is the case, consider the paths of two conference finalists last season. Going forward, the Bulls and the Thunder have a leg up on just about every team in the NBA, not because they spend a lot (which they don’t), but because they drafted a superstar and don’t have pay him superstar money.

Thanks to the rookie scale that keeps salaries artificially depressed for several years, the Thunder paid Kevin Durant, the NBA’s leading scorer, about a third of what the Jazz paid for Andrei Kirilenko last season. Similarly, the Bulls paid Derrick Rose, the league’s official MVP, about a third of what the Magic paid Gilbert Arenas, the league’s unofficial LVP.

Paying Durant $6 million is an enormous competitive advantage on its own, but the real benefit here is that it frees up Oklahoma City GM Sam Presti to spend money elsewhere when he needs to. The opportunity cost of paying Arenas is that you forfeit the chance to use that money on other things (like a James Harden or a Serge Ibaka or a Russell Westbrook).

This concept isn’t unique to NBA general managers. Do you pony up $30,000 for a fancy car or do you buy a slightly less fancy car and deposit the leftover cash into a savings account to help send your child to college? NBA teams face a similar choice when choosing to spend their money.

With a soft cap on payroll, it becomes imperative to spend your money wisely, and if you study successful franchises, those who spend money wisely seem to be bargain shopping at the draft.

The data reveals the truth

So, a couple franchises got lucky with drafting superstars and now they happen to possess bright futures and tight budgets. Big whoop, you say.

I’m with you. Just like I’m not satisfied with reducing a complicated topic to a line about the Lakers and Kings, pointing to the draft successes of the Thunder and the Bulls shouldn’t sit well with the rational reader.

So let’s roll up our sleeves and dig deeper. Many people have claimed that the draft is incredibly important to long-term success but the trouble has been backing up that assertion with hard data. Before we can talk about the significance of the draft, we first must have the tools to accurately measure draft success and go beyond anecdotal evidence.

To that end, it’s worth pulling up the draft value database behind the D.R.A.F.T. Initiative project from a couple years ago, which was an ESPN.com Insider series that analyzed the value of the NBA draft. The study tried to learn about the draft by tracking the career paths and production of every player drafted since 1989.

One of the discoveries during that project was that the Spurs and Lakers were huge winners on draft day. Apparently, finding Tony Parker at No. 28, Manu Ginobili at the end of the second round and plucking Kobe and Andrew Bynum without picking in the single-digits helps lay down a dynasty foundation. But if you look at the list of the most efficient drafting teams (as in, making the most out of where they picked), you’ll notice that the best drafting teams tend to also be the best teams of the past decade. On the flipside, the basement-dwellers of recent times found themselves routinely striking out on the draft.

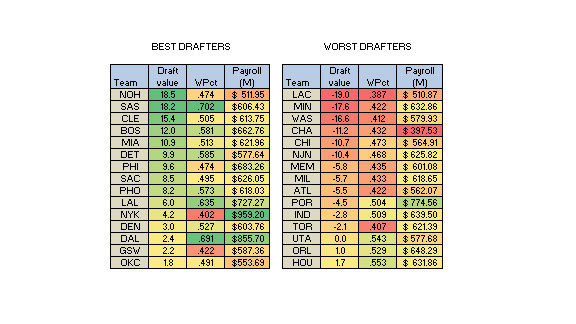

Here is an updated chart of the best drafting teams and the worst drafting teams over the past decade, along with their winning percentage and dollars spent over that time. Also, it is color-coded to make visualizing the data easier (greater the number, greener the cell).

What do we find? New Orleans, San Antonio and Cleveland have done the most with the draft over the past decade. The Hornets built a perennial playoff team on the cheap by picking Chris Paul at No. 4 and finding an All-Star at No. 18 in David West. They squeezed out 18.5 wins above what we’d expect from their draft slots over the years. The Spurs built a championship core out of their picks. And, yes, the Cavaliers may have lucked into LeBron James, but they also found Anderson Varejao at No. 30 and Carlos Boozer in the second round.

More importantly, notice that four of the top six drafting teams have won a title this past decade while the other two have come very close to playing for the Larry O’Brien trophy.

And the worst drafting teams? Yikes. The Clippers, Timberwolves, Wizards and Bobcats represent the doormats of the NBA and it’s no surprise that they’ve been drafting terribly as well. Many of these teams have been gift-wrapped prime opportunities to draft franchise players, and instead, they selected Adam Morrison and Jonny Flynn. Even drafting an MVP in Rose didn't completely erase all the misfires the Bulls made in the early 2000s.

Now, the colors tell an important story. Strictly looking at the draft value and win percentage, you’ll notice lost of greens clustered together and reds clustered together. This hints that the two go pretty much hand in hand. If you draft efficiently, chances are you’ll be in good hands.

But look at the third column of data which tells us how much money they’ve spent over that time. It’s subtle, but the pigments aren’t as closely connected.

What we’re seeing is a strong tie between drafting efficiency and win percentage, but not so much for winning and payroll. In fact, draft efficiency alone explains 34 percent of the variability in a team’s record over the past decade. How much does payroll explain?

Just 7 percent -- a tiny amount in comparison.

Many economists have studied the issue of payroll and competitive balance. Andrew Zimbalist, an economist at Smith College who has written several books on sports economics, recently told the New York Times, “The statistical correlation between payroll and win percentage is practically nonexistent.” That 7 percent is what he’s talking about.

What it means for competitive balance

Of course, we knew all along that the draft is important, but now we see it as an absolutely critical ingredient to the championship recipe. If payroll predicted championships, then the Knicks would have a dynasty by now. Instead, they largely ignored the draft, sold the lottery picks to other teams and look what it got them: a blood-red cell in the winning percentage column.

In order to be competitive in the NBA, you don’t necessarily need to have a lot of money, but you absolutely need to be smart with your money. And the smart money tends to be in the draft. When Stern says the system is broken because of the disparity in payroll, feel free to listen to the Lakers-Kings comparison but also note that the Thunder has been able to fast track success in a supposedly broken system.

Stern strives for a hard cap (or a punitive luxury tax disguised as one) and claims his pursuit is for the good spirit of competitive balance, but a closer examination shows that payroll and winning are not directly correlated.

What we've learned is that spending is cyclical. The smart organizations, like all businesses, try not to spend until they need to. As an example, the Boston Celtics' payroll the year before they formed their Big Three? It ranked 19th in the NBA. The year before that it was 21st. They lost over 100 games over those two seasons.

The NBA might contend that the Celtics weren’t winning because they weren't spending. But we must be careful about confusing cause and effect here. It may also be the case that the Celtics weren’t spending because they weren’t winning. Why throw big money at free agents when it won't really move the needle for title contention? Perhaps it is better to keep costs low until you can swing a big trade or increase your chances to land a superstar in the draft (see: Thunder, Spurs, Bulls).

Teams run into trouble by buying average players in a free agency market that usually comes with a "winner's curse" premium. If you spend money just to spend it, you find yourself in the in-between world that the Detroit Pistons, Toronto Raptors and Golden State Warriors currently occupy. As we’ve seen time and time again, if you want to be competitive, follow the lead of most champions: build through the draft and be smarter with your cash.

Of course, it helps to have more cash, which allows teams to be more flexible and spend when they need to spend. But if there’s a disparity of haves and have-nots in the NBA, the real disparity can be found in management, not dollars.