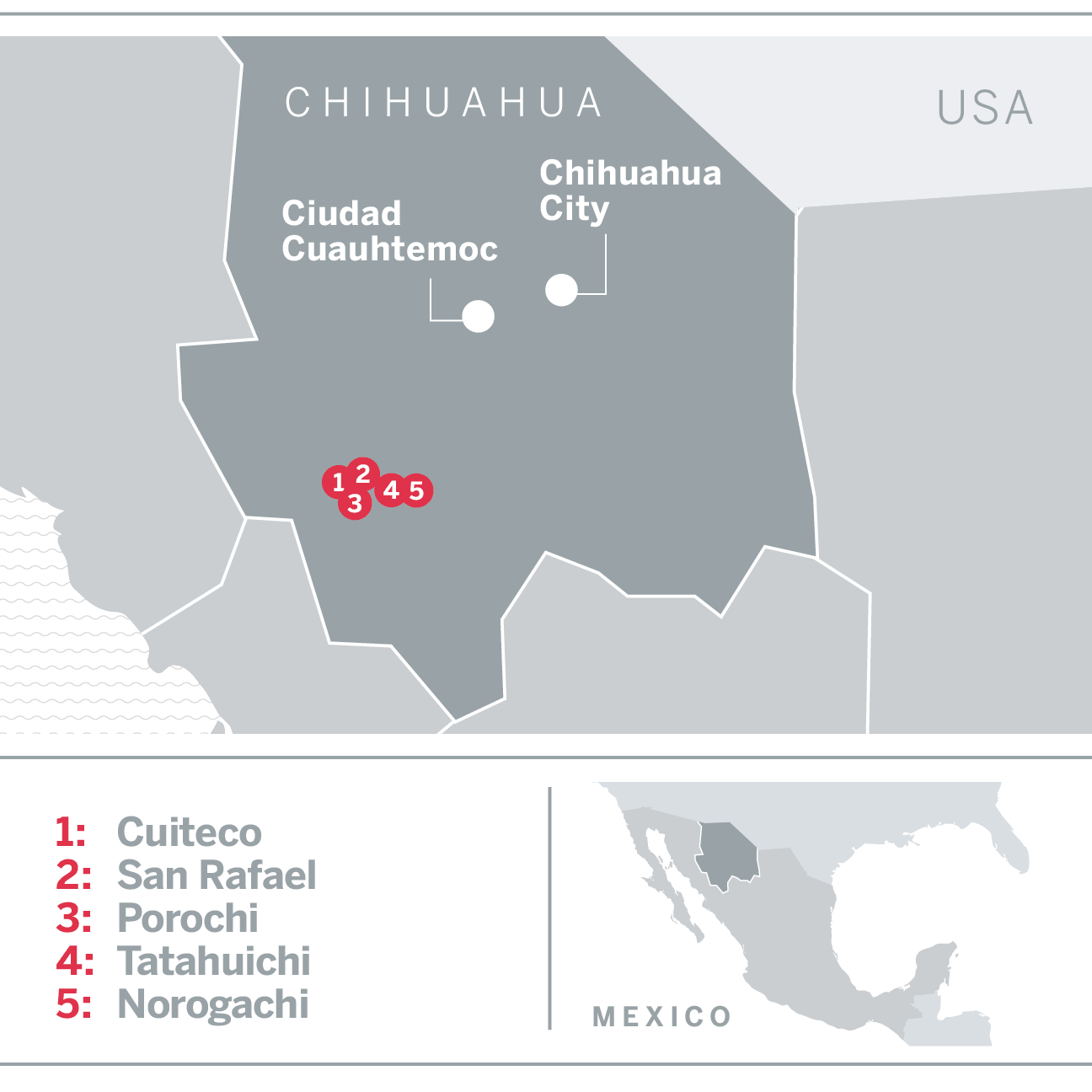

SIERRA TARAHUMARA, Mexico -- This region in the southwest portion of the northern border state of Chihuahua is known for its natural beauty. Here, among canyons, forests and mountain peaks, the indigenous Tarahumara people, often called the Raramuri, have lived for centuries.

Life is difficult in this picturesque but impoverished area, with high unemployment, low opportunity and rampant drug cartels having prompted many Raramuri to flee the isolated villages in their ancestral homeland. But not all choose to run away; some just run.

For decades, the Raramuri's only means of transportation between remote, far-flung communities has been by foot. This culture of extreme travel, born from necessity, has translated fluently to the field of competition. Raramuri runners, often lacking modern athletic gear, have found success in ultramarathons up to 100 kilometers (about 62 miles), including a 22-year-old woman who earlier this year topped a field of 500 runners from 12 countries to win a 50K race while wearing huarache sandals and a traditional skirt.

"The Raramuri runners remind me a lot of the famous Kenyan long-distance runners," former marathoner Carlos Ortega said in Spanish. "They've also learned how to turn the difficulties of their circumstances into a talent, the talent to run."

Although the Raramuri have mastered extreme distances, they've fallen short in even the longest of Olympic events.

"They need to learn how to run shorter distances, faster," said Ortega, who is on a mission to transform the Raramuri's inherent ability into success at the Olympic level. "No one was teaching them how."

Until now.

After nearly a decade of seeking financial backing, Ortega last year secured funding from the Telmex Foundation, one of Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim's philanthropic organizations, for a program to train the country's indigenous athletes for Olympic-length races. He has since been working with more than 500 runners in six states. Few have shown as much promise as the Raramuri.

THERE ARE AROUND 125,000 Raramuri living in Mexico, according to Mexico's National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples. Ortega and his coaches work with 16 teams spread across the Sierra Tarahumara, and he believes that a handful of those runners have the potential to compete in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. Catalina Rascon, 17, is the top prospect in the program. She won her first 60K race when she was 12 years old and her first 100K at 14.

Catalina grew up in the remote village of Porochi, but a year ago, she moved to Chihuahua City, the state capital, to continue her education and train in better conditions. She lives with her older brother, Guadalupe, who is her primary coach in the program.

She arrived at the city's training facility wearing a pink blouse with blue flowers, a long, multicolored dress and white huaraches, the traditional handmade clothes of her culture. It's the type of outfit she wore when she started competing and what many Raramuri athletes still wear for races, but Catalina now prefers modern running shoes and athletic gear.

"In the sierra, since we're little, we walk really long distances every day," she said. "Buses are uncommon and expensive. We don't have ways to move from one town to another. So we're used to walking. Often we just run to get there faster, but also because it's more fun."

Catalina recognizes that her affinity for extreme distances might be an obstacle to her accomplishing her stated goal.

"My dream is to run in the Olympic Games," she said. "I know it's going to be difficult to compete against people that have been training their whole lives for the Olympics. But I'm working hard to be able to compete against them."

The issue for Catalina -- and other Raramuri runners -- has been that the longest Olympic race, the marathon, covers "only" 26.2 miles (around 42 kilometers), a distance at which Catalina was usually just finding her rhythm. Two Raramuri marathoners ran into the problem while competing in the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics. After finishing 32nd and 35th, they complained that the race was too short.

"Because of their running style and way of life, they have very strong endurance, but their cruising speed is very slow," said Ortega, an engineer by trade who wrote his thesis on training techniques for indigenous runners. "For longer races, their slow pace eventually overtakes their competitors as they get tired, but in shorter races, the Raramuri pace isn't fast enough to win."

Ortega has Catalina focusing on events between 800 and 10,000 meters, distances contested in the Olympics but rarely entered by Raramuri. She's won races in Mexico at 1,500, 5,000 and 10,000 meters in the past year, but it's a long road to 2020. The Mexican Olympic Committee doesn't have its own program to develop Raramuri athletes, so it's up to Ortega to get his runners to that level. Catalina and other hopefuls would have to qualify in future events designated by the Federation of Mexican Athletics Associations before becoming part of the country's national team.

"The best marathon runners in the world are the Raramuri," Ortega said, "and if they learn how to effectively run shorter distances, Mexico is going to win a lot of medals in the future."

JESUS MANUEL CERVANTES, known to all as Chepe, had overseen Ortega's program in Chihuahua. Although not a Raramuri himself, Cervantes -- who recently suffered a stroke and has been unable to work -- was a longtime physical education coordinator throughout the state. Traveling from town to town in that capacity. he took a special interest in the Raramuri, organizing dozens of trips for runners to races around the country, as well as in the United States and Europe.

Chepe's expertise made him the perfect tour guide for a journey over the highways and dirt roads of the region to meet some of the program's most promising runners this past summer. While passing through several towns, he pointed toward the large mansions behind gates that seem oddly out of place in poor mountain areas.

"A lot of gangsters here," he said.

Men stood on the side road with guns tucked into their belts yet visible. In one restaurant, a wide variety of hats bearing the number 701 were for sale, making it clear which criminal group controls the region. The logo represents the Sinaloa cartel, which adopted the number after its now-incarcerated leader, Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman, was named the world's 701st richest man in 2009 by Forbes magazine.

The mountain range that runs through the states of Chihuahua, Durango and Sinaloa is known as the Golden Triangle, famed for its production of marijuana as well as poppies, the base ingredient in heroin. There have been reports of cartels forcing the region's Raramuri to transport drugs.

Despite that backdrop, extreme poverty is a more pressing concern for the locals than the threat of criminal activity.

In the tiny mountain community of Tatahuichi, several Raramuri approached Chepe. A woman holding a baby asked for bus fare to take an injured relative to a doctor's appointment. Another complained about the lack of food. A sense of desperation permeated the town.

"It's difficult for the runners to train while trying to support their families and communities," Chepe said. "There's a lot of problems in these towns. We still need more support and help, more invitations to international races, so that these runners can help improve their communities."

Onorio Juarez and Silverio Ramirez walked an hour from their small ranches to Tatahuichi so they could meet with Chepe and talk about their experience in Ortega's program.

"A lot of people have left to work in the cities. There's no jobs here -- just poverty," said Ramirez, one of the program's older Olympic hopefuls at age 34. He said many in the community travel to pick fruit during certain seasons, while others work as maids in cities such as Ciudad Cuauhtemoc, Chihuahua and Juarez.

The two men hope their athletic prowess can someday provide something positive for their people.

"If one of us reaches [the Olympics], all the [Raramuri] will be able to feel it as well," Juarez, 25, said.

Juarez and Ramirez then demonstrated a game called rarajipari, a kind of ball-kicking race that has been played for generations in their communities. Although sometimes a contest between villages, the game is typically played by the Raramuri as a way to pass the time as they travel long distances.

They take turns using their huarache-clad feet to lift a wooden ball and launch it forward in one swift motion. The other then chases it down and launches it forward. It's easy to imagine the Raramuri doing this for hours on end while making their way between the isolated communities.

THE TOWN OF NOROGACHI is nestled deep in the sierra. Although the population is fewer than one thousand, the village is sprawling in the eyes of 17-year-old Raramuri runner Antonio Ortiz. He, along with his with his new bride and his father, walked seven hours to Norogachi from their community, which consists of only 10 houses.

Chepe brought Antonio and his father, Roberto, into a classroom of students between 12 and 14 years old who might qualify for the training program in the future. He explained Antonio's accomplishments and told of how Roberto won a 100K ultramarathon in the '90s. The children looked on in awe, with one young girl loudly saying "wow."

"You are your own worst enemy," Chepe told the students -- not to admonish but to motivate. "When you don't believe in yourself, when you don't believe in what you can accomplish, you hold yourself back."

Antonio speaks little Spanish -- he began learning only two years ago -- and embodies many of the qualities typical of the Raramuri. Although the Mestizo Chihuahuenses have a reputation for speaking brashly and loudly, a trait common in the cowboy cities of northern Mexico, the Raramuri are known for their mild demeanor.

"Day to day, I work in the fields in the mornings. It's very hard work," Antonio said in a nearly inaudible whisper outside the school. "Then in the afternoons, I train. But on Sunday, I don't work. I train all day."

Antonio recently won a 10K race in Mexico and is the top Olympic prospect in Ortega's program at that distance. But he seemed confused when the topic turned to the Olympics. When Chepe reminded Antonio about the conversations Ortega had with him during a visit about a competition among countries around the world, Antonio nodded vaguely.

"Sometimes the Raramuri know little outside of their communities," Chepe said. "It's hard for them to understand the magnitude, the global scale of something like the Olympic Games."

IN OTHER PARTS of the sierra, a modernization of sorts is taking place. In San Rafael, a town of roughly 2,200 in the municipality of Urique, the youth are more urbanized, likely influenced by the tourists who stop there while traveling via the popular train that traverses Mexico's expansive Copper Canyon, which runs through the Sierra Tarahumara.

Luz and Gerardo Quezada embody this transition. Luz, 13, prefers to be called Lucy; Gerardo, her 16-year-old brother, goes by Jerry. They wear modern clothing. On this day, it was jeans and a sports shirt for Lucy, and a Puma T-shirt that said "Jam" and basketball shorts for Jerry. Neither wears sandals.

"For those that are accustomed to the huaraches, of course it's more comfortable," Lucy said. "But for us, running shoes are better."

Lucy proudly recounted a number of races she won and claimed she raced only once in traditional Raramuri clothing, saying she found "the skirt to be a bit uncomfortable to run in."

The Quezadas represent the youth movement of Ortega's program, which focuses on training runners from an early age for Olympic-distance races rather than ultramarathons. The siblings specialize in races between 2K and 10K and speak eagerly about the Olympics, well aware of the event's global importance.

"Since the program began, we've been able to train better, improve, go to more races," Jerry said. "We're both hoping to compete in Japan."

In San Rafael, a minor hub in the Raramuri region, the students can train on a baseball diamond with a running track that traces the fence, but not all the communities are so lucky.

In the tiny village of Porochi, where houses disappear into the trees and cellphone service is spotty or nonexistent, aspiring runners make due with a makeshift training ground. Jose Luis Concheño, the local trainer for Ortega's program there, helped the kids construct a track outlined by stones that had been painted white.

Concheño's brother Carlos is the program's trainer in the nearby town of Cuiteco. The brothers bring their runners together for meets every few months.

"The kids are training every day, but to really improve, they need to have competitions," Jose Luis said. "If there's no competitions, they can still develop, but this gives them a little extra."

Carlos arrived for a meet over the summer slightly late with a group of older teenagers. In Porochi, there is no junior high or high school. After elementary school, kids in Porochi and surrounding communities must live in youth shelters in Cuiteco if they want to continue their educations.

The children spent the day in the hot sun racing on the rudimentary track. Teachers at the school gave handmade medals to the winning runners, who wore them proudly around their necks like the Olympic champions they dream of becoming.

The Concheño brothers hope some of the Raramuri children will at least be able to improve their existence through the program.

"Maybe they can see the world, have a bit of a change in their lives and their education, maybe get a scholarship," Carlos said, "because there's a lot of issues here."

AT AGE 6, Alfonso Gonzalez dropped out of school after six months to work in the fields. He didn't start running competitively until he was 21, but he quickly started winning races. He's 31 now and hopes it isn't too late to make a life for himself and his family by running.

Gonzalez left the sierra a year ago with his wife, two daughters and niece to work in the apple fields outside of Ciudad Cuauhtemoc. A Mennonite farm owner took Gonzalez under his wing after learning he was a top Raramuri runner. The family lives in a small room with a single mattress in one of the owner's factories, and Gonzalez is allowed to work half-days so he can train in the afternoons.

"It's the dream that I have now, to participate in the Olympics," said Gonzalez, who knows he needs to improve in "shorter" races. "Endurance, I already have that. What I'm missing is more speed. That's what I'm training now."

He admits that he knows nothing of Japan, that he has never heard of sushi or Mount Fuji. But with the guidance of Ortega's program, Gonzalez believes he can experience the faraway country in person at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

Dreams such as Gonzalez's, as well as the conviction that helping the Raramuri and others like them become better runners will give them better lives, are what make Ortega passionate about his program.

"I really believe in this project," he said. "It will give them the opportunity to see the world, to be role models for their communities and to inspire hope for the indigenous and Mexico as well."