|

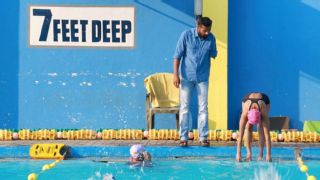

Shamita UN can't tell a gold medal from a bronze. She can't write or count. But she finds the will to wake up at daybreak and head to the pool for swimming sessions each morning without the lure of reward. Shamita, 16, has intellectual disabilities: She's diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), typically characterized by inattentive, restless and impulsive behaviour particularly in new or challenging social and emotional situations. At a recent "swimathon" in Bengaluru, Shamita is strikingly calm. It's an unfamiliar setting; the people milling around, schoolchildren roughly her age, are unknown to her and she's the only specially-abled athlete in the fray. She adjusts her pink swimming cap and matching goggles with practiced ease before plunging headlong into the pool. And she's completely at home. "If she's in water, we know there's no need to worry," says her father Nagesh Kumar, watching from the sidelines. ******* Swimming's regimented and sequential nature - defined start and end points, a clearly-marked lane within which to swim - makes it best suited to bring structure to a child's focus, particularly for those with ADHD. Swimming has in fact fostered a marked improvement in Shamita's behavioral skills over the past four years, her father vouches. At the Swimathon, she completed 21 laps in the stipulated 30 minutes, 18 laps shy of the top finisher. Either way, numbers aren't something she comprehends or cares too much about. Her father wears a contented smile as she glides out of the pool. "She may not be a great swimmer but at least she's trying. The least we can do as parents is encourage her," he says. It's in the experience though, that Shamita says she finds joy. "I love competing," she says, "If I swim more my health will improve and I'll become taller."  She won two golds and a bronze at the National Special Olympics swimming meet in September last year. She's unaware, though, of the link she shares with one of the greatest sportsmen ever - multiple-time Olympic champion swimmer Michael Phelps, who was fidgety and could barely sit still in class and finally diagnosed with ADHD. His mother then goaded him to take swimming lessons to help him expend all the energy that kept him jumpy through the day. The idea proved to be winning. The only answer she offers reflexively is the one on her favourite sportsperson: "Sharath anna (elder brother)," she says, smiling. A visit to the Pooja aquatic center in Bengaluru where Shamita trains helps us learn why. ******* "OK, double arm backstroke, shoulders should touch your ears. I want both hands together." Sharath Gayakwad's voice rises above the sound of splashing waters, his right arm held up straight against his ear, index finger pointing heavenwards. In place of his left arm, though there's just a rolled-up sleeve. The words '7 feet deep' are painted on the wall behind him in big, black bold letters. Shamita's head bobs above the water, taking in the fresh batch of instructions. Sharath, born with a deformed left hand, is one of India's most accomplished Paralympians who coaches close to 80 kids, of which eight are differently-abled, three intellectually disabled. Shamita is one of them. It makes for a unique, heartwarming sight. "I started coaching Shamita around two years ago," he says, "She was already swimming quite well so it made my job easy. The challenge is to always improve and she's surely come a long way from where she started."  To engage the specially-abled, making training sessions fun is often the winning way. "I'm not one of the best guys to put fun into training but we do have a lot of sessions like relays and games like water polo which can help them enjoy," says Sharath, who finished with six medals at the 2014 Asian Para Games, the highest by an Indian at a multi-discipline event, "None of it is pre-planned though. For instance, if we feel that one of them is having a low day we make training more fun to cheer them up." Shamita trains with a batch of able kids twice a day, daily and it helps her push her limits. "The other kids too know that they have a specially-abled peer amidst them, but it doesn't change anything," Sharath adds. "They're together as a team which makes it easier for me to give them workouts and manage sessions." Sharath began coaching four years ago, having realized that his love for teaching the sport was far more enduring than his fire for competing. Among the many things he's mindful of in his duties as a coach for kids of differing abilities, a chief one is to use the sport as a unifying factor. "For me it's not about wins or medals. They have their own world where they want to accomplish something. I just want everyone to swim. Swim together," he says. ******* The Swimathon was thought up last year by Hriday Sahgal, a Class 12 student of The International School, Bengaluru, as a way of offering specially-abled athletes an opportunity to share the platform with his able-minded school mates. It taps into sport's potential to foster inclusion of those with disabilities, which, apart from changing community perceptions, also empowers those with disabilities to look at themselves differently. Last year's event was a Swimathon inaugurated by specially-abled athletes; this year, it was a triathlon-based format with unified competition in three events - seven specially-abled athletes competing alongside TISB students in swimming, running and cycling events. The idea was welcomed by Special Olympics Bharat (SOB), the national sports federation which reaches out to and offers training and competition opportunities to the intellectually disabled in India.  The event had a large element of charity: sponsors had pledged a certain amount of money for every length of the pool swum or rounds of the field run or cycled in 30 minutes. Student volunteers in their all-blue school uniforms kept track of the lap count, which was directly proportional to the amount of funds raised. Last year's Swimathon raised more than Rs 15 lakh; this time it hovers close to Rs 6 lakhs. The proceeds are being used by SOB to fund similar initiatives. "Last year we had three specially-abled athletes swimming four lengths of the pool to inaugurate the Swimathon. This year we thought integrating the field and increasing participation by adding two more events would be a better idea," Hriday said. "We had 120 participants divided into 40 teams for three events this time as opposed to 50 participants for the Swimathon last year. It's definitely a step towards our goal of a more inclusive community." For his role in introducing his school and peers to the Special Olympics concept, Hriday was picked to represent SOB at the Youth summit in Graz, Austria, at the same time as the World Winter Games. Hriday who's now in his final few months of school before he moves to a university, is keen on keeping the initiative alive and has introduced his juniors to the process hoping that its scope can be expanded in the years to come. "Last year when we first conducted the Swimathon, I initially found it difficult to interact with the specially-abled athletes. But we connected really well once we started talking about swimming. That was a lesson for me on how sport can act as a bridge. It helps break all barriers."  A competitive swimmer himself, Hriday first struck up this initiative after his own performances began feeling uninspiring and hollow. "Though I kept winning, I didn't feel the same anymore," he says, "I thought what better way than to leverage my talent and give back to society in a both unique and effective manner." ******* In his closing instructions for the evening, coach Sharath commands, "Two laps easy," pulling the yellow divider floats out of the pool with his right hand, the sun's fading orange bouncing off the waters. Freed from the confines of their lanes and the expanse of the waters thrown open to them, a crowd of kids swims across its breadth; Shamita soon disappears into the sea of floating skull caps. This is her milieu, where she can be just one among many.

|