The UFC is spending the entire month of May outside the United States, visiting Brazil, Chile and England in consecutive weeks. And with MMA being such a diverse and international promotion, it makes sense to bring live events to new markets. But that's primarily a business strategy. What happens to the fighters -- such as Darren Till on Sunday in his hometown of Liverpool, England -- who are competing in cards around the world?

Home-field advantages in sports are often silently implied among sports fans, but they rarely are corralled by anyone other than quants and sportsbooks. Home teams do, in fact, win more often than visitors in a variety of sports, including soccer, basketball, baseball and football. And the mechanisms for the edge works through a variety of pathways.

In some sports, crowd noise favors the home team either by interfering with the visitor's ability to communicate with teammates, or by influencing the types of calls that referees make in the game. There is also a time zone effect. In the United States, West Coast teams underperform when traveling to Central or East Coast time zones, where biological factors are compounded by the other disadvantages of playing on the road. There also are subtle but powerful physiological and psychological impacts of traveling to a new place, living in a hotel, eating new food and, in general, doing things outside the normal routine.

If these forces affect entire sports teams, surely they must affect individual-sport athletes as well.

Exploring the home-cage advantage

The sport of MMA has sample-size problems in many ways, complicating detailed causality. But for fans and MMA bettors, a simple look-back analysis of home-cage performances in the largest UFC markets does offer insights into how venue location may affect athletes.

But first, we need to acknowledge that not all fights are created, or matched up, equally. Especially early on, the UFC hoped for fight cards in new geographies that not only featured local fighters but also saw them win. They wanted fans from new markets entertained, not bitter. Wins for the hometown fighters were great for the arena atmosphere -- and for future ticket sales. So it's reasonable to assume that matchmaking would favor home-cage fighters -- but also that betting markets would recognize it.

In this decade, and looking at three major MMA markets, we do see a difference in betting odds for home-cage favorites. American fighters competing in the U.S. are essentially our "baseline" for the home-cage advantage. The UFC was primarily a U.S.-based sport during the rapid rise in popularity of the mid-to-late 2000s. Everyone competed in the U.S., and almost entirely in Las Vegas. But home-cage American fighters facing foreigners in the past decade averaged pick-'em odds, confirming that the market didn't really see any consistent matchmaking bias for the local fighters.

Not so for fighters with a home-cage advantage in Brazil or Great Britain. Though events were far fewer, home-cage fighters in these markets were favored in general. British fighters on average closed as minus-122 betting favorites (or minus-112 at "true odds," minus the house vigorish). The Brazilians, however, saw the clearest favorability, averaging minus-146 favorites (or minus-134 at true odds).

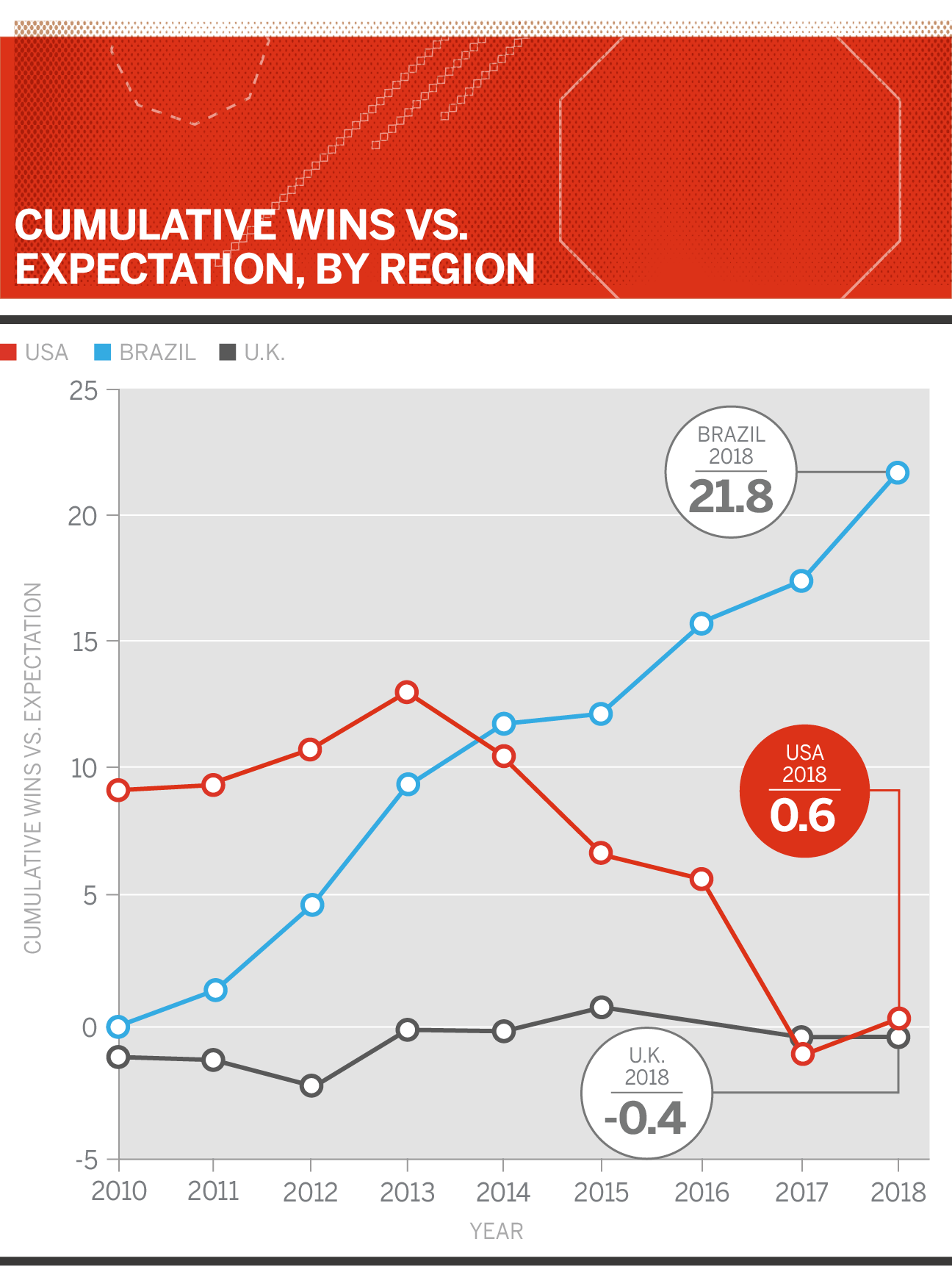

So whether it was favorable matchmaking, or just the views of the betting public, there was a slight difference in how home-cage fighters matched up in Brazil and the United Kingdom. But how did they perform against those odds? If home-cage fighters were slightly favored on the night, and according to odds should win, say, four fights out of seven fights, how many did they actually win?

The results paint a clear picture of a Brazilian home-cage advantage and a lack of any effect in Great Britain. After subtracting the vigorish, any bettors consistently taking home-cage fighters would lose money in the long run in the U.K., and also the U.S., while the performance of Brazilians still would beat expectations. American home-cage fighters early on had slight underdog odds, which they outperformed, but that trend flipped and the effect since has evened out.

The results paint a clear picture of a Brazilian home-cage advantage and a lack of any effect in Great Britain. After subtracting the vigorish, any bettors consistently taking home-cage fighters would lose money in the long run in the U.K., and also the U.S., while the performance of Brazilians still would beat expectations. American home-cage fighters early on had slight underdog odds, which they outperformed, but that trend flipped and the effect since has evened out.

The cause of the effect is up for debate, but until these trends reverse, it's easy to understand why some fighters are reluctant to fight in Brazil. The takeaway this weekend in Liverpool is that the locals don't seem to have any advantage over visiting fighters. They never did, and they still haven't deviated far from expectation. In fact, in the only U.K. fight card so far this year, British fighters were expected to win exactly three of seven fights on the card against foreign opponents, and they did exactly that.

For the main event in Liverpool, Till opened as a mild underdog to former welterweight contender Stephen Thompson, but lines have recently evened out. Yet even that movement still shows an average betting line of plus-117 (true odds) for U.K. home-cage fighters this weekend. That means the average home-cage fighter is an underdog, expecting 4.1 wins out of 10 matchups versus foreign opponents.

As with any trend, things can always change. For fans in Liverpool, they might just want to create their own intimidating chants to mirror the hostile Brazilian arenas if they want to see their home-cage fighters outperform expectations.