|

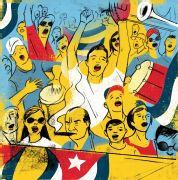

When he was a teen in the late 1940s, my uncle Tito tells me, it cost 40 or 50 cents to go to a baseball game at El Gran Stadium in Havana, which would be like $5 or $7 now. "So what was it like?" I ask him. "What were the snacks? Did you drink beer?" "Wellll," he says. Tito is a handsome fellow in his 80s, and as always, every word he says sounds a little naughty. "See ... when you went to the stadium, you were busy all the time. It's not like you sit there and you have a beer and a hot dog. Forget it. You'd bet a quarter on each play! Does he get to first base, or ..." "You were betting the whole time?" "Yeah. So you'd be in the game. You know what I mean?" That is the Cuban attitude toward baseball. One way or another, we're in the game. I learned about the game mostly from Tito's dad, my grandfather Pipo, a lifelong aficionado who emigrated from Havana to California in 1958. In a very close family, I was particularly close with Pipo. He was widowed in 1970 at the age of 71 and then was looked after -- "spoiled" might not be entirely the wrong word -- by a large gang of adoring relatives, myself included. His children -- Tito, my mother, Consuelo, and their sister, Carmen -- are reminiscing with me one recent afternoon over Chinese takeaway at my mom's house in Garden Grove. In Cuba, baseball is generally known as pelota (ball). The game is an institution that binds Cuban families and communities. At the deepest heart of it, baseball in Cuba is an emblem of resistance to -- and eventual freedom from -- the island's Spanish colonial masters, but that is another story. For my family, it's one of the strongest and most comforting connections between Havana, the beautiful place they left, and an unfamiliar new world. Baseball helped make California into home. Twice in his life Pipo escaped from extremely hairy political situations. As a teenager in Tenerife, Spain, in 1916, he resolved to avoid any part in the Moroccan conflict, dodged the draft and took himself to Cuba, where he eventually established himself in a modest way in the cement tile business. He fell in love with his laundress's young daughter, my grandmother. They raised their family in the working-class Havana neighborhood of El Cerro, three blocks from where El Gran Stadium would open in 1946. In the early 1950s, my grandfather came to Los Angeles to do a contract tile job at the Ambassador Hotel and he fell in love with California. By the time Fidel Castro came to power in 1959, our whole family had immigrated to Long Beach. They didn't know that there would be no going back.  For me, baseball is intimately connected with the lovely summer feeling of being safe and happy, and the anticipation of having really delicious soup for lunch at my grandfather's house. The games I'd watch with him as a young child helped form my idea of "safe." After a struggle, a race, you lunge for this very small space, a straw-filled canvas bag, heart pounding -- and for a little while, nothing can touch you. A feeling, a scene you'd imitate in parks and at school during PE, wearing a neat little blue uniform with your name stitched in white thread over the breast pocket. On television, the fantastically dressed umpire's hands spread wide in that unmistakable gesture, so full of drama and justice. So full of life. Safe! Though twice uprooted, Pipo had the most admirable and successful life of anyone I've ever known. He was a working-class guy who had near-absolute independence until his peaceful death at the age of 87. He had a long and happy marriage and a loving family. His home was small but his own, all paid for, with a bit of garden where he grew magnificent roses and tomatoes and puttered around, fixing things, growing things, with his huge, powerful craftsman's hands. There was a weathered wooden shed in the back, cool and dark inside, smelling of earth and filled with mysterious artifacts and implements for gardening and building. There was a yard in front that he mowed himself, a tiny kitchen whence marvels arose every day. His very good friend, Mr. Oyama, slightly younger and likewise widowed, lived across the street. He'd come over for a little whiskey, and they would tell jokes, shared in an incomprehensible pidgin of their own decadeslong devising. (Pipo spoke no Japanese and Mr. Oyama spoke very little Spanish. They both loved baseball, though.) In the sitting room, in a blond wood cabinet opposite a strategically placed reclining chair, sat the television, whose chief purpose was to bring news of the Dodgers. There was a ritual for watching baseball games: The sound would be turned all the way down by means of a knob on the front of what people still called "the set." The console stereo against the opposite wall had an AM band, and Vin Scully would be turned all the way up for the duration of the game. I must have been in my 20s before I realized that my grandfather, who barely spoke English, had always been so particular about this. I later learned that many other grandparents and parents were in the same habit, denying the TV announcer his voice in favor of the radio titan (who would one day become a TV titan too). Something in Vin Scully's voice embodied everything fun, not just in baseball but in the world. Everything safe. When Mimina, my grandmother, was still alive, there were many large, lazy family gatherings at their house on the weekends, with the women in the kitchen gossiping and making arroz con pollo or carne con papas or congri, and the men in the living room watching the game or playing dominoes or arguing about politics. Later everyone would gather to eat, and then there'd be Cuban music and maybe a little dancing. Every day in the summer a gaily painted ice cream truck drove past my grandfather's house. It didn't play one of those awful calliope songs, chiming instead with a solitary, slightly mournful-sounding bell. The driver -- for years the same quiet, portly man -- sold soft-serve ice cream of the most delicious quality, dipped in chocolate if you liked. There was also a plain gray moving van that came once or twice a week, a mobile Japanese grocery with impossibly exotic products inside, including my favorite Botan Rice Candy, with the rice-paper wrapping so delicate, the candy within so lushly soft and toothsome. There were a lot of Japanese people in my grandfather's West Long Beach neighborhood. I remember walking past the splendor of so many front yards with small cypress trees pruned into romantic, windswept forms, stone figures or even a tiny, red-lacquered bridge. Only years later did I understand that many of these families, including Mr. Oyama's, had been among the 120,000 Japanese-Americans forcibly removed from their homes and interned during WWII, mostly in the spring of 1942. Many lost all their property as a result, forced to sell everything at ludicrous prices in the few hours they had before being imprisoned. At Mr. Oyama's funeral, Tito says, he learned a lot of things we hadn't known about him before: Mr. Oyama had been a judo teacher, a mandolin player, a fisherman. To us, he was someone Pipo loved, a delightful guy, round of face and physique, a big joker. (A favorite family story has Mr. Oyama shouting, "Hey! Watch my culo!" when my brother nearly backed into him one day as he was parking his car.) But Mr. Oyama was someone who also had been uprooted. I was too young then to understand how this goofy, charming character could possibly be concealing such a loss. My grandfather's loyalty to the Dodgers wasn't only a matter of affiliation with his new home; the Dodgers had a real link to Havana too. The Brooklyn Dodgers trained three times in Cuba in the 1940s and were treated like royalty there. My mom, aunt and uncle couldn't remember whether Pipo watched them play in Cuba; it's too long ago. But Pipo loved coming to LA to see the Dodgers play in the 1960s and '70s. Tito and my late father would luck into especially good tickets sometimes through work. My dad was a barber to several guys in professional sports, and Tito was a shop steward and foreman at a local can factory. "One English guy, he kinda liked my dad," Tito tells me. "And he would get me tickets. We got seats behind ... or not behind, but almost inside the dugout, with the Dodgers." He becomes so youthful and animated remembering this. "And Garvey would be in the batter's box and 'Look! Look, look! Six! Six! Galbi! Galbi!!'" (I took a particular interest in Six myself, as I recall, as did many of my fellow tweens. Steve Garvey was fantastically handsome.) Over many years I came to realize that the deeper meanings of baseball, particularly as it was once played in Cuba, with its ethical frameworks of freedom, beauty and egalitarianism, informed my grandfather's thinking more than politics or religion ever did. Pipo taking his time -- over choosing vegetables in the market, or slicing them up in the kitchen, or setting up the radio to watch the game -- took on a certain ... I don't want to say gravity, because he was all about relaxing and enjoying life, but more like he conducted himself in a way that indicated to me these things were important, and worthy of patience and attention. This soup? Important. Likewise this baseball play. Harmless and lovely things, pleasurable things, were also serious things. He modeled, but never explained, a way of thinking, a way of living that is central for me even now. I could say that my grandfather's philosophy is mainly a matter of taking your time, just like in baseball. You do a lot of thinking as you go, and you try to acquit yourself well in even the smallest detail. In my mind, Pipo was -- is -- invincibly a just man in an unjust world. I would be sitting on the sofa, you know, maybe trying to learn to crochet, not really paying much attention to the game. But I don't think, before or since, I've ever been so at peace as I was then.  When Pipo got really sick, we had a caregiver come in for him, a lovely young woman of 30 or so named Blanca. She had a shy, sweet smile, raven hair and a lustrous complexion, and Pipo fell in love with her instantly. She was meant to be shopping, cleaning and cooking for him, but you'd go over there and he would be fixing her lunch, while she sat quietly at his little yellow Formica kitchen table, smiling radiantly, as if in on a private joke. What amount of money would have been enough to pay for such a return of happiness near the end of his story? Blanca would sit and watch television, including baseball, with him for ages, no doubt. She was hopeless at the stuff she'd been hired to do and a champion at all the rest. I miss him so much, still. When I go home to Long Beach, there are a lot of old haunts from my childhood and teen years I still visit from time to time. Acres of Books is closed now, but the Hof's Hut on Bellflower is still serving "Those Potatoes," which are basically hash browns with minced peppers and onions. You can still go to the Queen Mary, the Art Theater, the museum and Joe Jost's. But for my Cuban family, all their home places were lost forever after they came to California. Whatever could be salvaged from their past had to be brought in memories, photographs, habits, music. Baseball, and the ideas that come with it. My mom's face and Tito's light up just talking about El Gran Stadium, where the chief rivalry was between the two biggest city teams, Almendares and Habana. Blues vs. Reds. My mom used to like Cienfuegos ("Hundred Fires"), she tells me, which was a regional team from a legendarily beautiful part of the country -- Yasiel Puig's hometown, in fact. "That was my grandfather's team. But that was sentimental. ... My heart was for the Almendares." There would be big fights over baseball, she says, when she went on tour as a dancer all over Cuba. Were there fights in the stadium? "Oh yeah," they chime in unison. People wouldn't get beat up too often, but there was a lot of yelling. "I didn't fight," says my mom, primly. "But I was mad." It's been a real solace to remember my grandfather lately, not least because he experienced very perilous economic and political conditions, including two world wars, and made it through to peaceful and prosperous times-a fine old age with no bitterness, his sense of humor still warm and sweet as a child's. So many times it must have seemed to him that the whole world had gone irreparably off the rails. How must he have felt in 1916, in 1940, in 1959? But he just figured something out and got on with his life. Somehow it all worked out fine. May we all have Pipo's luck. Like in the old Spanish toast: Salud, amor y pesetas, y tiempo para gozarlos. (Health, love and coin, and time enough to enjoy them.) All my life, Cuba was described to me as a wonderful place that has been ruined, which is why I've never wanted to go. It also goes against my conscience to visit tourist places where I can go enjoy things that the people who live there can't. But when I saw the Obamas doing the wave with Cubans in the stands at a baseball game during their visit in 2016, I thought for the first time that I might like to go one day and do that too, and try to recover something of my grandfather there, something of my family's long-ago life. In the video of the Obamas' visit, MLB chief baseball officer Joe Torre says, "I think the two countries, the one thing they agree on, for sure, is how much they love the game." My grandfather would have loved that, I know. Baseball is a refuge for people of goodwill to connect with one another in a terrible world, and that's what it will always mean to me. Tito tells me a story about a colleague from work, Mr. Evans, who would come over now and then. "You remember my father's hands?" he begins. Well, obviously! Pipo's fingers were as thick as knockwursts. To this day I've never seen stronger hands; he'd have me hold up my relatively doll-sized ones against his and laugh and laugh. "Well, Mr. Evans was the same way!" Tito says. A big guy, apparently -- and a Reds fan. "So I would take Mr. Evans to see my father, and they would shake hands. And my father would say [growling here] 'Datchherrrr.'" ("Dodgers," that is.) "And Mr. Evans would say [also growling] 'Cincinnattah.' "And they would squeeze a little tighter. And you could see these fingers ... purple! They weren't white, they weren't red, they were purple. And they would go, 'Cincinnattah!' 'Datchherrrr!' and then they'd pat each other on the back." "He was really funny," says my mom. "Oh, he was something else," Tito says. "My dad was something else."

|