|

Are you only as good as your worst player, or are you only as bad as your best player? These are the two sides of a nerdy debate about how soccer works that's been simmering among weirdos like me for the past decade. On the side of the first question, we have the authors of "The Numbers Game," Chris Anderson and David Sally. In their book, they put forth the "weak-link theory" of soccer: that the qualities of each individual player don't just get added up and divided by 11 to produce an aggregate of team performance, but rather that the qualities multiply with each other. So, great players make other great players even greater, while bad players can make great players average. One hundred multiplied by zero is, well, zero. Through various analyses, Anderson and Sally found that improving your best player by 10% will roughly result in a five-point improvement from season to season. Except, they found that improving your worst player by 10% will lead to a nine-point improvement. If you believe that soccer teams are complex systems -- a multi-dimensional interplay between 11 players making thousands of decisions across every 90-minute match -- then the logic makes sense. However, if you've watched Lionel Messi play for Inter Miami CF, then that logic makes no sense. Arguably the best soccer player in the world joined what was inarguably the worst soccer team in MLS, and they've outscored their opponents 25-11, won the Leagues Cup and remain undefeated through Messi's eight games with the club. This all raises an interesting strategic question that's rarely applied to soccer. In the NFL or the NBA, you'll often hear about or see teams doing everything they can to shut down one star player, whether it be a receiver or a star scorer. "We're going to make someone else beat us," coaches say. Given its dynamic nature, soccer doesn't really work like that, but considering how much better Messi is than everyone else, should an MLS team try to completely neutralize Messi at the expense of protecting against all of his teammates? And if they did, what might it look like?

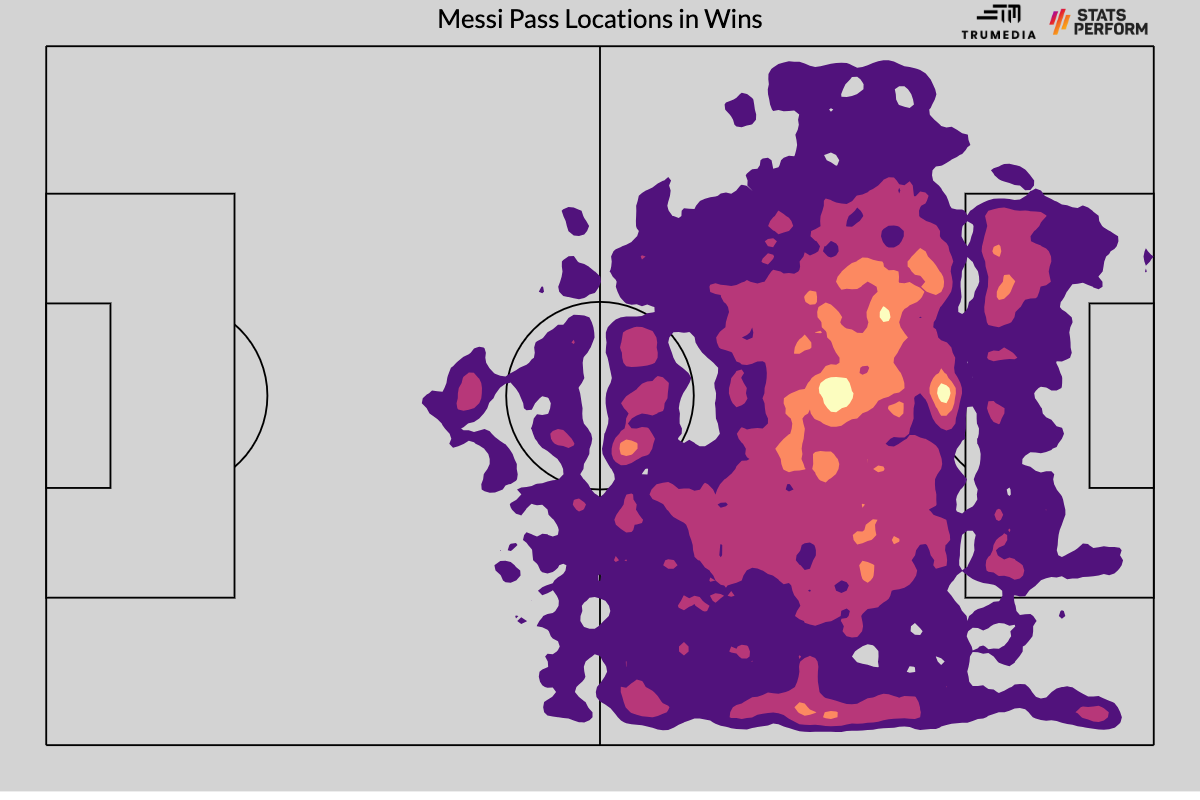

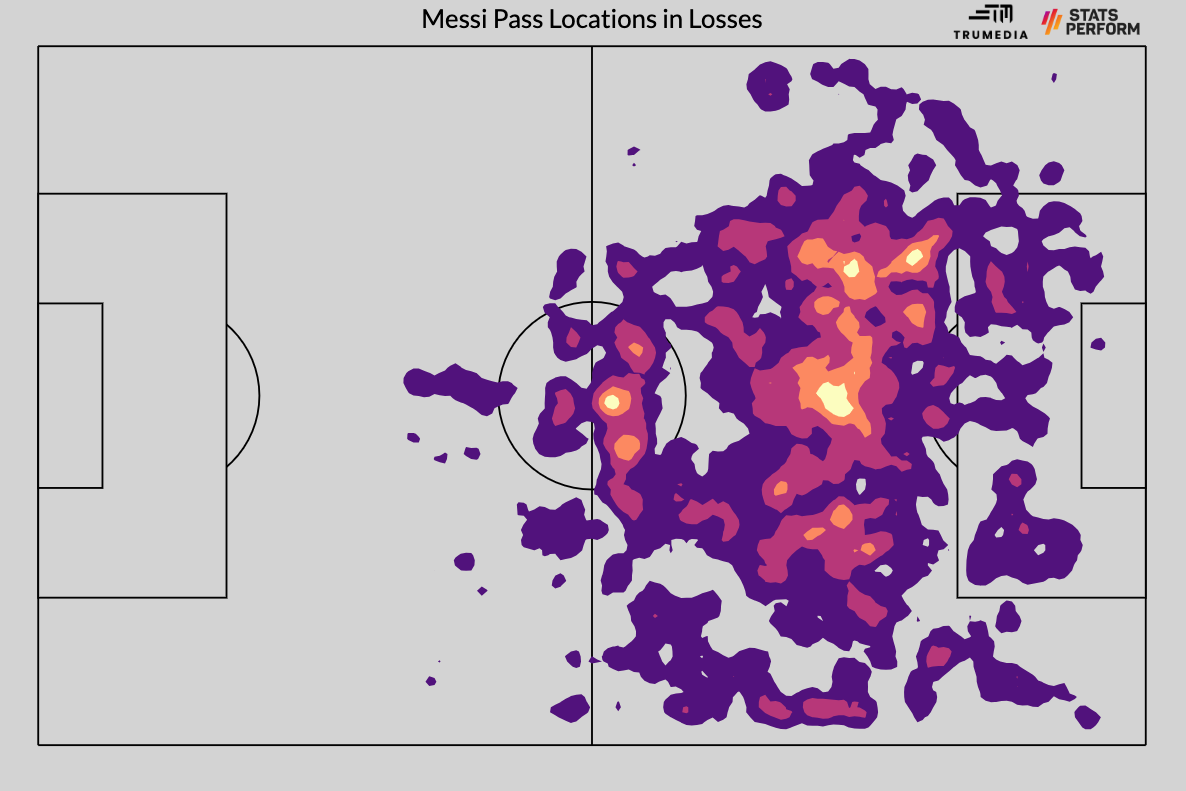

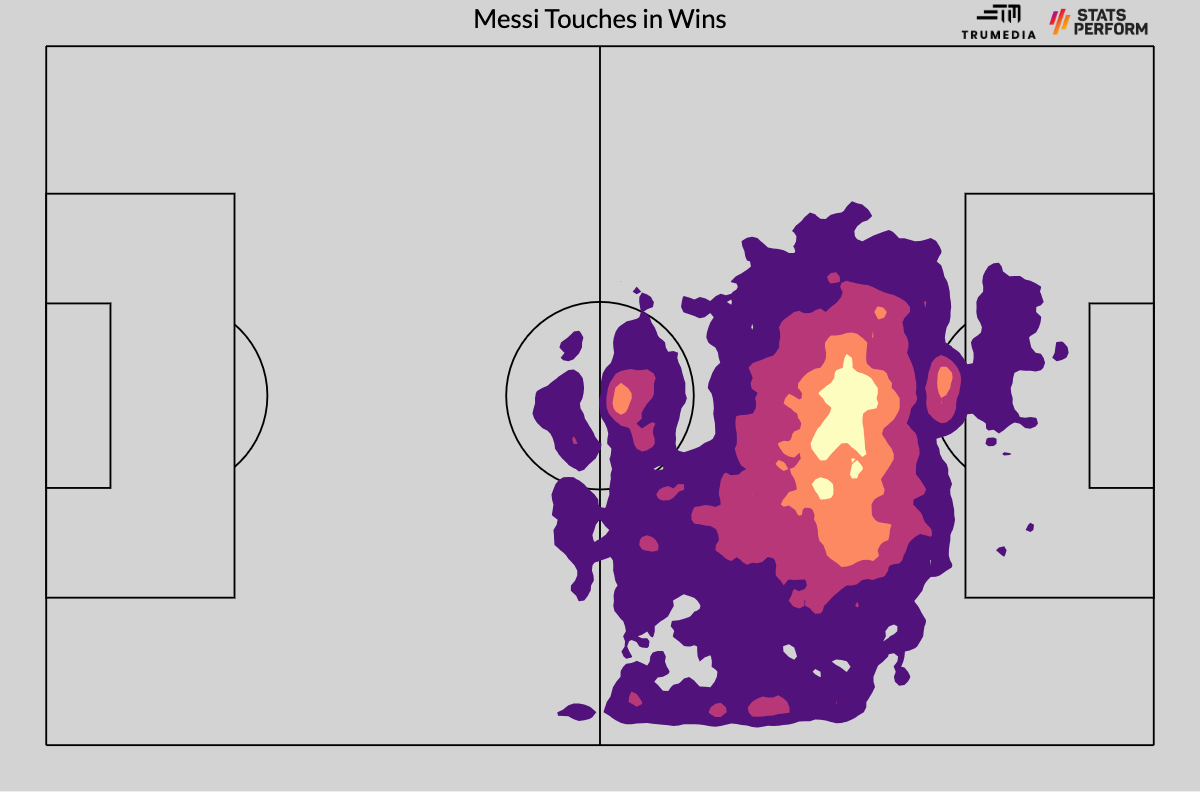

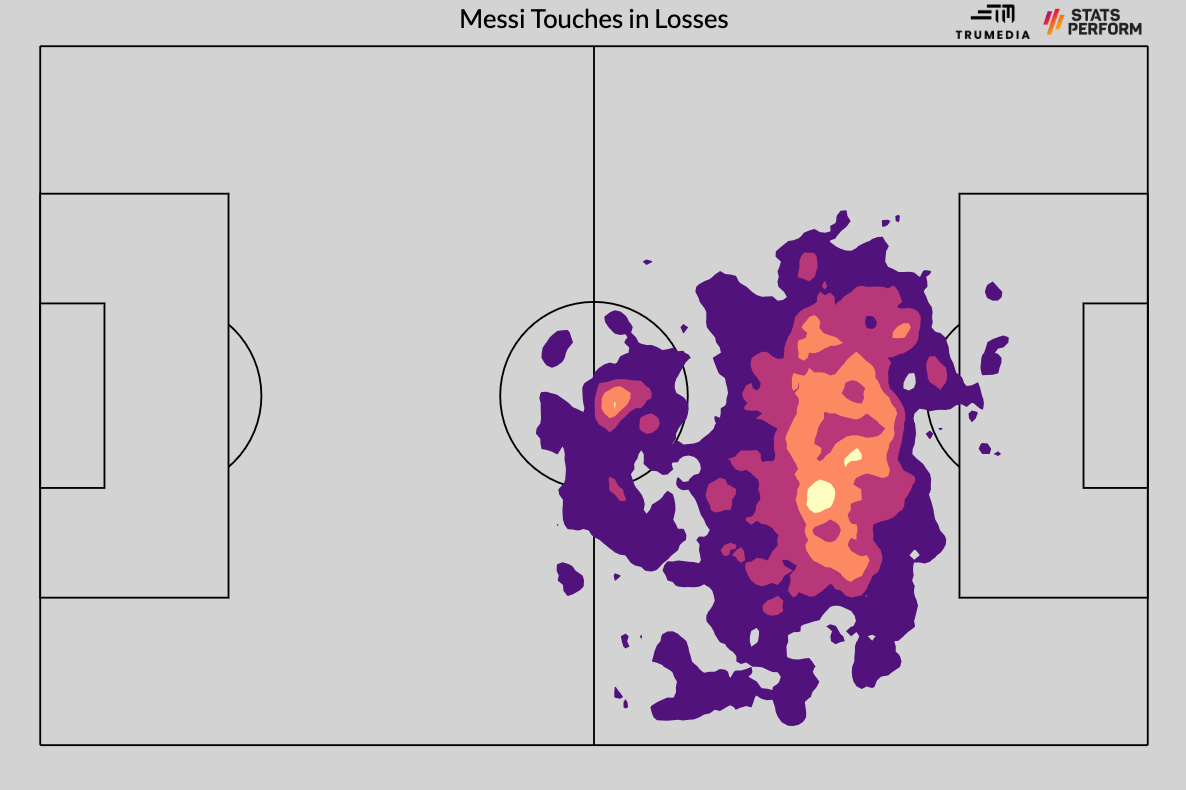

What happens when Messi loses?According to Stats Perform, Messi played 434 league games in Europe from 2010 onward. His record: 316 wins, 44 losses and 74 draws. I'm not sure which framing makes those numbers seem more ridiculous: that he won 73% of his matches or that he lost only 10% of them? Point being: Lionel Messi's soccer teams have rarely ever lost soccer games. But is there anything that all of those losses have in common with each other? What makes Messi the greatest soccer player ever -- and maybe the greatest athlete -- is that he not only produced goals and assists at a much higher and much more consistent clip than any modern player, but he also was better at dribbling than anyone and better at playing balls into the penalty area than anyone. He was also better at aiding in possession play to move the ball up the field than anyone else, too. And so, unlike a low-touch-but-high-impact player like Kylian Mbappé or Erling Haaland, you'll pretty much never get a game in which Messi doesn't have some kind of positive impact on proceedings with the ball at his feet. Therefore, it seems like a large part of the battle here is just to make it so Messi is having that impact further away from the goal. You're just not going to ever have a game where Messi isn't getting on the ball, so if you can force him to drop deep and try to dictate play from the midfield, that, historically, has been a big win -- even if it meant he picked apart your backline from deep and you still ended up getting annihilated. In this heatmap of the end locations of all of Messi's passes in wins, you can see that he's constantly driving the ball into that left half-space at the top of the box, and then he's constantly hitting diagonals into the left side of the penalty area:  Now, these images are a little tricky to compare, given that there are way more passes in wins because there are so many more wins, but just focus on the areas of density in this next image. There's a cluster of passes near the center circle -- a good chunk of which comes from the fact that Messi was taking more kickoffs in losses because his team was conceding more goals -- but then there's not as much concentration in the left half-space. And more than that, there are fewer passes being completed into the box: 4.9 per 90 minutes in losses, 5.3 wins.  The heatmaps of his touches tell a similar story, too. In wins:  And in losses:  In wins, he's able to camp out on top of the box in the center of the field; in losses, his distribution of touches is scattered more across the width of the box. And then there are just way fewer touches inside the box: 8.0 per 90 in wins, 5.5 in losses. On top of that, there are fewer shots -- 5.3 in wins, 4.8 in losses -- while there are more passes into the final third in losses (8.7) than in wins (8.1). He's also more creative in losses (0.24 expected assists) than in wins (0.19). In that sense, FC Cincinnati executed on a solid gameplan Wednesday night, as the teams that have beaten Messi in the past have turned him into more of a passer than a shooter. "[Messi] always has a response for every moment of the game, regardless of the difficulties he has," Inter Miami manager Tata Martino said after the game. "I think that today he did it more as an assister and not as a finisher." Of course, as Cincy eventually found out, just because something is a "better" option doesn't necessarily make it a good one. Messi had two assists in the second half to cap a two-goal comeback, and Inter Miami eventually won in penalties. Can you neutralize Messi?So, let's say you saw Messi terrorize the Leagues Cup with his goal scoring, and then you saw him pick apart the first-place team in MLS with his passing. You weren't comfortable with either scenario, so you opted for a third way: completely sacrifice the rest of your team in order to make sure Messi almost never touches the ball. The first question: Is this even possible? Much of Messi's brilliance comes from his understanding and anticipation of space. He walks better than most players run; this is not a glib statement, this is scientific fact! There was a "viral TikTok" -- I can't even begin to explain how embarrassed I am to type those words, in that order -- from Miami's Leagues Cup final win, where Messi is just kind of wandering around, barely moving, is he injured? Is he alive? Then all of a sudden he sprints to the left corner of the penalty area, and bam, the ball is in the upper corner. "One thing Messi told me is to stand still more," 19-year-old Miami midfielder David Ruiz said after the Leagues Cup final win against Nashville SC. "You want to run for every ball, look for space to have it more, but he has told me to stay still in my position and the ball will come to me. I tried it and it came off. I was more patient." Part of Messi's standing these days, at age 36, occurs when the other team has the ball. He's constantly staking out and then occupying high-value positions where he can then receive the ball as soon as the opposition loses it. So, in order to mark Messi out of a game, a team would first need to sacrifice one of their attackers to follow Messi around even when they have the ball. Otherwise, he'd easily lose his marker and constantly find the ball in transition moments. Would that be enough? No, definitely not. Only Messi knows where he's going, and he knows where to go better than anyone else. A constant marker would definitely limit Messi's pure on-ball impact, but he'd still get plenty of touches, especially as the game wore on and this player started to lose energy. One way to counteract that would be to sub the marker off at halftime and bring someone else in, but even that wouldn't be enough; Messi frequently does amazing things when defenders are covering him across various situations in every game. This wouldn't fully eliminate his impact. Now, you could just have two players follow him around for the whole game, but then you're playing 9-v-11 with the ball, and you're still playing 9-v-10 without it if we accept that this approach eliminates Messi's impact -- and I'm not even sure that it does. But let's take a somewhat more conservative view of this. You have one guy follow Messi around all game, but then you also tell your other defenders to defend Messi how they normally might in a game: pick him up if he floats into your area. We'll call this a "hybrid double-team" -- you've got the one guy following him around wherever he goes in and out of possession, and then you've got whatever other defender is in that area bracketing him as a second defender. Let's say that this works, right? You make a sub at halftime, and you use two of your most athletic players to follow him around, 45 minutes each. Throw in the second defender, and Messi just doesn't touch the ball much at all. You can't stop him from finding possession after fouls or corner kicks, but let's say you limit those, and you also avoid giving up any free kicks around the box, which almost seem like they're penalties for Messi right now. If you do that, we'll call it playing down 1.5 men. It's not quite two men down, because you're eliminating Messi and that second defender is only joining in defensively, but it's also more than just playing a man down. So, we'll split the difference. Is that worth it? - Stream on ESPN+: LaLiga, Bundesliga, more (U.S.) According to work by the analyst Mark Taylor, if a Premier League team gets a red card in the first minute of a game, it's worth about 1.45 goals over the course of a match. I don't quite know the best way to calculate that second half-man, but I'm going to add another half onto that total. (I feel OK about this because I think there might be an exponential effect to losing players from the 11, rather than just a linear one.) So, if we do a little rounding, we'll say that essentially playing a man and a half down for a full game is worth 2.15 goals per game: 1.45 plus another 0.7. In MLS this season, the best per-game goal differential is St. Louis City's at plus-0.8, while the worst is the Colorado Rapids down at minus-0.8. In other words, the difference between the best and worst teams in MLS is 1.6 goals per game. The cost of marking Messi out of existence is that, plus another half goal or so. That's absurd, and I'm not sure it's not worth it. Without Messi, Inter Miami were the worst team in the league. With him, can we be sure they're not a half a goal better than whoever the previous best team was? They're probably not, but pretty much any time there's even been the sliver of a possibility that Messi might do something previously unthinkable, he's gone out and done it. You've seen these first eight games. Has anything really changed?

|