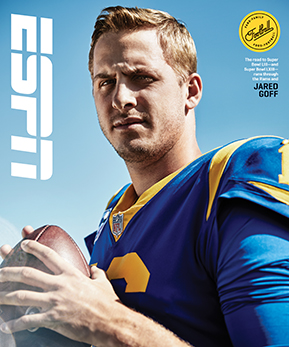

The California Cool of Jared Goff

In the midst of a wild three-year career arc that has taken him from rookie bust to MVP candidate, the Rams quarterback has learned to enjoy the ride. How far can his surge lift L.A.?

A version of this story appears in ESPN The Magazine's November issue. Subscribe today!

Not long ago, the keepers of football's sacred texts detected a tragic flaw. The college game was spreading out and speeding up. It had become too simple, too bloodless -- and the repercussions could cripple the NFL. What they were witnessing was an insult to the thousands of men who sacrificed their bodies and brains on the game's altar. A quarterback standing 15 feet behind the center, catching a snap and throwing the ball to a receiver before the defense could even react? This was an act of pure expedience, a shortcut in a sport that does not abide them. Who was left to teach a young quarterback to nudge up close to the center, put his hands in another man's haunch and take a proper snap? A quarterback should be close enough to feel fear, and to smell a nose guard's rancid breath, and the suggestion that these gimmicky offenses would work in the NFL -- against grown-ass men, they thundered -- was an affront to the legacies of every great American who ever took the time to teach a man the seven-step drop.

But one by one, the thundering old men were replaced by younger men who identified an opportunity within the perceived decay, and the sacred texts began to be rewritten. These new men, unburdened by the psychic lore of Joe Namath's creaky knees or Joe Montana's jigsaw-puzzle spine or Y.A. Tittle's bleeding forehead, took the obvious skills of the spread quarterbacks and set them loose against NFL defenses.

And now what is this we have before us -- fun? Yes, a league that can't define a catch without seven pages of footnotes is being overrun by this most endangered concept. Fun destroys the myth that everything must be difficult and exhausting and earned. Fun puts the game's inherent martiality at risk. Turns out you can make your way down the field faster, more efficiently and far more often by standing back there and finding the receiver most open.

It's starting to feel like a revolution, and every revolution needs a frontman. Rams quarterback Jared Goff, under the progressive vision of head coach Sean McVay, is the leader of one of the NFL's most dynamic offenses. Just two years after 2016's top pick suffered through the turgid, sclerotic final days of the crumbling Jeff Fisher empire -- losing all seven of his rookie starts -- Goff is an ascendant star, an MVP candidate, a player who symbolizes the promise of the new over the stubbornness of the old.

"It's funny that the spread quarterback was seen as such a scary thing going into every draft," Goff says. "I played in the spread, Patrick Mahomes played in the spread, Deshaun Watson, Mitchell Trubisky -- the NFL is so stuck in its ways sometimes. If you don't innovate and adapt, you're going to be left behind. It's about coaches; how do you get the best out of your players? It's not by forcing someone to run what you want to run. It's how you can make A the best A can be."

This was a moment -- adapt or die -- and it called for something that's not exactly rampant in the NFL: men with the vision and confidence to change the paradigm. As it turns out, they didn't come to kill the game; they came to save it.

The Rams scored 224 points in Goff's rookie season. They passed that mark in Week 7 this year, en route to an NFC-best 299 in their first nine games. Hana Asano for ESPN

The first time I saw Goff play quarterback, he was a sophomore in high school, so skinny he had to wave his arms to make a shadow. Even then, with his Marin Catholic jersey billowing around him, the ball left his hand and traveled audibly through the air, and those watching lifted their heads and tracked it in dumbstruck silence, none more helplessly than the thick-ankled defensive backs trying to track it down.

Through 39 wins over three varsity seasons, a silly percentage of his throws ended with the receiver jogging into the end zone and Goff jogging nonchalantly to the sideline in that same upright two-beat trot you see now, as if throwing 50-yard touchdowns was just another way to spend an afternoon. He always gave the impression he was waiting around for something that -- finally -- might be worth celebrating.

"I've always said the same thing about Jared," says his father, Jerry, a former big league catcher. "If you walk into a stadium in the fourth quarter and you had no idea what was going on, you wouldn't know if he had thrown four touchdowns or four picks."

Now the game is infinitely faster, the men playing it so big and strong they can be mistaken for machines moving across a screen. Goff has traveled the distance from skinny to thin -- "I know how to fall" is how he explains his durability -- as his game has embarked on a consistently upward trajectory. The Rams, 11-5 last season, were stung by the wild-card home playoff loss to the Falcons; after a revelatory second season -- 3,804 yards and 28 TDs -- Goff started slowly in his first playoff game and never got rolling. This year, after an 8-1 start, the memory of that loss had him eager to talk about the one or two games in which the Rams' offense started slowly before starting to roll. He roams the sideline during the slow times repeating the same message: "It'll pop." In every game, even the Week 9 loss at New Orleans, he's been correct.

There's a common reason prescribed when young QBs start reading defenses and identifying coverages and throwing to the right receiver through the narrowest of slots. McVay says it first: "The game is slowing down for Jared." It's accepted wisdom, but in reality the only way for the game to seem slower to the quarterback is for the quarterback's brain -- through repetition and recognition -- to accelerate.

"If I can look out over a defense and say, 'That route's not going to be there,' then I don't need to spend a lot of time on it," Goff says. "It allows me to get through everything a little quicker."

That works well with McVay, who coaches like he's always trying to beat the yellow. He plays defensive back against his receivers at practice and talks so fast that punctuation never has a chance. He exists in the realm of lines and angles, the world an equation that must be solved before time runs out.

"He does something every day to amaze me," offensive tackle Rob Havenstein says. "The details he picks up are incredible. He'll pop into our meetings and tell us why we're doing this or how we're changing this. He'll leave, and we'll sit there and look at each other for a minute, shaking our heads, and then someone will say, 'Yeah, that'll work.'"

The NFL has become a cult of coaches and quarterbacks. You can't win without a guy who can play the position and a guy who can teach it. One has to be able to command a room, the other a huddle. The Rams are unique; Goff and McVay's combined age (56) is 10 years less than Bill Belichick's, and McVay, at 32, is younger than two of his starting offensive linemen.

"I don't think you can put an age to what his brain does," says center John Sullivan, who is five months older than McVay. "His brain is just his brain. It could be 10 or 110 -- doesn't matter. Not everything around here fits with tradition when it comes to age."

I ask McVay if he can cite specific throws Goff has made this season that show his growth. It feels a little cheap, like a dad asking his kid to recite baseball stats at a holiday party, but let's face it: The temptation is too great. McVay, famously, is someone who can be asked about random plays and recount the details like they're the names of his siblings, so asking him to provide some concrete examples of his quarterback's improvement seems like an ethical imperative.

He doesn't have to think. The throw is right there, playing on a screen in his mind:

"I look at the timing and rhythm with which he threw Josh Reynolds his second touchdown against the Packers," he begins, setting the scene from the Rams' Week 8 win. "You want to be able to throw that three-stage footwork -- he tempos his drop on a three-step-from-the-gun footwork and lets it go when his back foot hits, recognizing the coverage concept. The difference between taking that and taking a hitch is a catch-tackle, or maybe a catch-incompletion, and a touchdown with a catch-transition."

Animation courtesy of NFL Next Gen Stats

I should probably tell McVay he's giving me too much credit with this explanation, but interrupting him when he's talking football seems like an unforgivable transgression. The way it looked to the untrained eye, though, tight end Tyler Higbee ran a short sit-down route to Goff's right, and Reynolds ran a deep slant in the seam behind Higbee. Just as a linebacker drifted toward Higbee, Reynolds split the two deep safeties and turned to find the ball arriving in his hands. Reynolds' explanation is less technical than McVay's, but it requires its own level of translation. "Once I saw the dime linebacker sit on the cheese [Higbee; think mousetrap], I knew the ball was coming before I laid eyes on Jared," Reynolds says. "As soon as I turned, the ball was on me." McVay was suggesting that last season Goff might have settled for the first open man -- Higbee -- for a modest gain, rather than waiting that extra second -- with the rush coming -- to see the play through to its greatest glory.

"In play-action, we run a lot of what we call three-level throws," Goff says. "Usually, it's something vertical, something intermediate and then something like a checkdown to a running back or a tight end. When I was just starting to understand things last year, it might have been" -- here he nods his head three times while moving his eyes higher each time -- "one-two-three. Mechanical. Now I can see before the snap: OK, that deep ball is probably not going to be open, so this throw is probably going to the intermediate guy. You start to play the percentages, see what's most likely going to take place."

The Rams won their first eight games for the first time since 1969 because the roster is loaded with great players: Todd Gurley is an MVP favorite (along with Mahomes), and Goff is in the conversation; Aaron Donald could repeat as defensive player of the year; Brandin Cooks and Robert Woods are on track for 1,000-yard seasons, as was Cooper Kupp before a season-ending knee injury. Reynolds, who will move into Kupp's role as Goff's third receiver, cites a less obvious reason why the Rams have been able to keep defenses guessing. "We're a really smart team," he says. "Everybody in here is smart, and that makes a difference."

The Rams' extensive playbook grows as the season wears on. McVay is free to introduce concepts midseason and knows they'll be understood. "Obviously, we're expected to know the plays," Havenstein says. "But they've been teaching us more about the why of it -- why we block a certain defense a certain way, why a certain play will work when the defense gives us a certain look. When you understand something, it makes it easier to add new stuff."

Each week, they're being taken deeper and deeper into McVay's brain, a hoarder's garage of expansive concepts, granular diagrams and, not least of all, slogans -- "We Not Me," "You Know What You Know," "The Standard Is the Standard." Those words can seem meaningless from the outside -- a mind-numbing expansion of the it is what it is culture -- but within the team, they represent a shared language to wall off intruders. You know what you know is McVay's way of saying, We know what nobody else does.

"I feel like I get a pretty good look inside his mind," Sullivan says. "He's a freak -- in a good way. I've seen the videos of him reciting plays."

Guard Rodger Saffold, at the next locker, interjects to tell Sullivan, "Just like you."

"No, I'm not like that," Sullivan says. "Not like that."

"Don't let him fool you," Saffold says to me. "He remembers, yeah he does. 'Hey, do you remember that play from 2009?' That's this guy right here."

"Nah," Sullivan says, embarrassed. "I can recall certain things. Probably not the way [McVay] can, though. I don't think anybody can."

"To play at the level he's playing is really impressive," says his coach, Sean McVay. "The level of throws, the understanding of what defenses are trying to present, the off-schedule plays he's able to make in rhythm." Ture Lillegraven for ESPN

The sibilant hiss of the word manages to compound the insult: System quarterback. Was it inevitable? Did McVay's ascendance require that Goff become an extension of his coach and not the curator of his own talent? Before the Rams' Week 7 game in Santa Clara, I listened to a 49ers radio analyst say that Goff couldn't throw a spiral before McVay showed up. And two weeks later, before Goff had thrown a pass against the Saints, Fox's Troy Aikman said, "When [Goff] signs his next contract, he should give Sean McVay 10 percent."

The storyline began to develop a year ago, when the Great Helmet Communication Conspiracy opened a window for those who were seeking sorcery behind McVay's methods. Goff was miked during a game, and McVay's voice could be heard in the background as Goff stood at the line and surveyed the defense. "People misconstrued it," McVay says. "They thought, 'All right, they're just getting to the line and telling him what to do.'" The communication between the coach and the quarterback cuts off when the play clock reaches 15 seconds, and McVay says, "Jared's making all the calls. He has the mastery of the offense."

System quarterback?

"To call him that is a discredit to all the good things he's doing," McVay says. "As coaches, you want to be able to put your players in a system that's conducive to their success. But there are 32 guys in the world that are starting quarterbacks, and it's a very, very elite group. And then to play at the level he's playing is really impressive -- the level of throws, the understanding of what defenses are trying to present, the off-schedule plays he's able to make in rhythm. I think sometimes that is received as, 'Well, a lot of guys can do what he's doing,' and I just don't think that's the case. I think he's doing some special stuff, and I think as a result of him playing quarterback he makes it a good system."

“He's doing some special stuff, and I think as a result of him playing quarterback, he makes it a good system.”

- Sean McVayThe system runs on balance, in scheme and in personality. "I think sometimes I can get too excited," McVay says, "and the consistency of Jared's demeanor helps me keep it in perspective. I look at him during games, so composed and refreshingly secure in himself, and I have to remind myself: Hey, that's what you want to be."

And while he's at it, McVay wants to know the system that could conjure what he saw in Minnesota, when Goff completed 26 of 33 passes for 465 yards and five touchdowns with no interceptions. It was one of just 49 perfect quarterback ratings (158.3) in the NFL since 1950. Only three of those were by quarterbacks with at least 30 passes thrown, and of all of them, Goff has the most yards and is tied for the most completions.

Statistically it could have been the best quarterback performance in history, and there was one throw in particular that nobody could believe. Late in the first half, with the Vikings leading by three and the Rams at the Vikings' 19-yard line, Goff rolled far to his right and lofted a pass off one foot. "He's throwing it away," Rams quarterback coach Zac Taylor thought to himself, adding now, "I was thinking about the next play." Instead, Goff was throwing a geometrically perfect pass -- the angle, velocity and location -- that somehow scissored between two defenders and landed in the hands of Cooper Kupp in the back corner of the end zone.

Animation courtesy of NFL Next Gen Stats

In short, says Taylor: "It was one of the most remarkable passes I've ever seen."

Less than 48 hours after the Rams have defeated the Packers on the last Sunday in October, Goff is being photographed as he walks around the team's complex in Thousand Oaks. November is two days away, yet the temperature is in the high 80s, the Santa Ana winds crackling through the hills like radio static. Locals instinctively check the hillsides, expecting smoke.

The Rams are the last undefeated team in the NFL, a few days away from their first loss, and Goff's most immediate concern is a stamp on the underside of his wrist from a Halloween party the night before that everybody keeps mistaking -- annoyingly -- for a tattoo. There's also a wrap on his left ankle and yellowing bruises on his left biceps. When the photographer asks him to sit on a curb for a pensive shot, he starts to bend down and then stops. "Can't do that," he says, shaking his head. Asked why, he laughs and says, "It's Tuesday." It's the only explanation needed. A few minutes later, he winces as he pulls on his jersey and pads. Task complete, he exhales the way you do when you finally catch your breath. "I'm only 24," he says, "but it's Week 9, without a bye."

Last year was Goff's rebuttal to being labeled a rookie bust, but this one feels like an arrival: on the short list for MVP, leading a team that expects to play through January. Hana Asano for ESPN

So much of the job is appearances. Quarterbacks like Matt Ryan stroll into a postgame news conference dressed like CEOs. Cam Newton does one thing, Aaron Rodgers another. Everyone has a brand, and Goff's can be loosely described as informal star. "Cali cool," Taylor calls it. When Goff first came into the league, he would arrive for a game, unbutton the first two buttons of his dress shirt, pull it over his head and bury it on the floor of his locker. So when he took to the podium after a game, he always looked a little like he was wearing ... well, a shirt that had been buried at the bottom of a locker.

He's more particular now -- he uses hangers, and his mom helps him with his outfits for home games -- but every once in a while, Jerry will dare to venture into the unknown.

"Jared, how about a suit this week?"

"Nah, Dad, I'm good."

Just two years ago, Goff was called a bust, and worse. ("You know what you know" is how he describes that situation.) Last year was his quiet rebuttal, but this one feels like an arrival: second only to Mahomes in passing yards through nine games, on the short list for MVP, leading a team that expects to play through January. He has helped to change the paradigm; he is part of the revolution.

It can be hard to tell. Goff's organic nonchalance transcends circumstance and outcome. Against the Saints, with just under 10 minutes left, he threw a 41-yard touchdown pass to Kupp to put the Rams a two-point conversion away from erasing a three-touchdown deficit. His reaction? The same as the one against Minnesota, and the same as the one throughout high school, which is to say almost no reaction at all. His dad says the most emotion he's seen from his son came in Seattle, after a successful quarterback sneak on fourth down late in the game clinched the Rams' fifth win. Havenstein, the offensive tackle, sits at his locker and mimics the most effusive Goff celebration with an almost apologetic fist pump and a strangled "Yuh!" It's modesty, sure, but that's only part of it. It's how confidence looks when someone is still waiting for a moment he deems worthy of celebrating.