OTL: Shadow Boxing

IAMI -- The old man opens the door and shuffles into a familiar room. The air smells of stale beer and discount brand cigarette smoke. The tables are taken by men with no names. They are all friends. They are all strangers. A different journey brought each of them here, to the pool hall on NW Second Avenue, but that doesn't matter anymore. Their journeys are over. Most don't share the details, not even their last names. Some don't remember the year, or how long they've been coming here. They have no past.

IAMI -- The old man opens the door and shuffles into a familiar room. The air smells of stale beer and discount brand cigarette smoke. The tables are taken by men with no names. They are all friends. They are all strangers. A different journey brought each of them here, to the pool hall on NW Second Avenue, but that doesn't matter anymore. Their journeys are over. Most don't share the details, not even their last names. Some don't remember the year, or how long they've been coming here. They have no past.

The old man walks clumsily to a table. He has a story. The act of telling it, of having people hear it, keeps him from disappearing forever. One night, he says, he fought Muhammad Ali. Almost won, he brags. Some believe him. Some don't. Most don't care. He's just another wacko wandering the streets with some tale about how his life could have been different.

They ignore him, pretending he's not even there. He's got to show them.

The old man gets up and throws punches into the air.

The people around him laugh.

He sits back down, invisible again.

PART ONE: LOST

In the beginning

The search started off six years ago with a phone call.

The man on the other end is Stephen Singer, a New Hampshire car salesman who collects things in his spare time. Most of all, he collects all things Muhammad Ali. It's a fetish. He prizes the light box he keeps on the wall of his office. With the flick of a switch, you can see an X-ray with a thin crack: Ali's broken jaw.

He tells me the story of the boxer who disappeared, starting by explaining his latest mission: Collecting the signatures of all 50 men who fought Ali. The first 35 or so came easy. Singer got a professional autograph collector to help with those. Then, the pro came to a dead end; Singer decided to continue on his own.

He peered into another world, in which a brush with fame didn't grant immortality. One by one, he found them. Some took months. He searched dank boxing gyms and dusty public records. He found a man who'd given up the ring for a European carnival. He located a notarized letter from a fighter turned Mafia hit man. A rabbi acted as a middle man in a small Argentine town for the passport of a fighter who'd been dead since 1964. He was No. 49.

One fighter remained. What had happened to Jim Robinson, who'd fought Muhammad Ali in Miami Beach on Feb. 7, 1961?

Singer tried everything. He contacted boxing historians and even enlisted Ali's old trainer, Angelo Dundee. He found a boxer in Philly named Jim Robinson … who never fought Ali. Private detectives and former FBI agents helped. Robinson was a ghost. He had no known date of birth, no known full name. No known family. No ties. No public records linking him to a place or a time. In the exhaustively well-chronicled life of Muhammad Ali, Singer has stumbled into the one hole, a man who'd shared a moment in time and space with one of the most famous humans ever, only to vanish. An old Associated Press story said Robinson was from Kansas City, which is why Singer is on the phone with the local paper's feature writer, who happens to be me. He tells me there isn't much more information to build on; nobody has ever really thought to search for the fighter before.

In a way, Jim Robinson didn't begin to exist until someone realized he was missing.

Hooked

Singer asks me to help, so I collect everything already known about Robinson. Turns out, although sports people throw around the phrase "go down in history" a lot, in real life, history doesn't amount to much. Jim Robinson's name appears maybe a dozen times in print.

The night of the fight, he ran into the Miami Beach Convention Hall, carrying an old Army bag full of his gear. The reason he seemed harried? He was a last-minute replacement, used to fighting for pocket change. The guy who was supposed to box that night, Willie Gullatt, didn't show.

Ali biographers figure Gullatt got scared. With good reason. Until that point, the old stories say, few considered Ali a great fighter. That all changed the day before he fought Robinson, when heavyweight contender Ingemar Johansson, in town training for a title fight with Floyd Patterson, invited the young Ali, still known as Cassius Clay, to spar.

They stepped into the ring, and by the time the men climbed out after two rounds, the history of boxing was forever changed. Ali threw a blur of punches, a jab, then two more, his feet dancing, a combination, right, left, right. Each punch landed -- hard. Johansson lumbered forward, throwing a roundhouse right, which didn't come close, and the big heavyweight stumbled and almost fell.

Ali danced and talked in rhyme.

The next night, Gullatt, who also seems lost to time, didn't show up. Jim Robinson got the call, even though Ali outweighed him by 16½ pounds. Robinson came out fast, throwing wild punches, which Ali dodged, waiting for an opening. About a minute into the fight, he saw his chance. Bam! Bam! Pow! Pow! The shots to the head put Robinson down. He struggled to stand, but the referee counted to nine, then stopped the fight.

It had lasted 94 seconds.

Afterward, the New York Daily News wrote, "It was all a mistake." The Miami News wrote, "If promoter Chris Dundee had canvassed the women in the audience, he couldn't have found an easier opponent for Clay."

Three years later, Ali beat Sonny Liston in Miami to become champion, and the next night, a few miles up the road in a tiny auditorium, Robinson lost to a journeyman named Jack Gilbert. Robinson was already fading away. Boxing records show he kept fighting, losing much more often than he won, finally stopping in 1968.

There's been only one sighting since then. In 1979, a photographer shooting pictures for Sports Illustrated went to find Ali's earliest opponents. Michael Brennan located Jim Robinson, whom people down in Miami called "Sweet Jimmy." Most of what's known about his life comes from the brief blurb that ran with the photos. He lived off veteran's benefits. He claimed he was born around 1925. He claimed he was wrongfully convicted of armed robbery. Most days, he just hung out in the seedy Overtown neighborhood, at the pool hall owned by Miami concert promoter Clyde Killens.

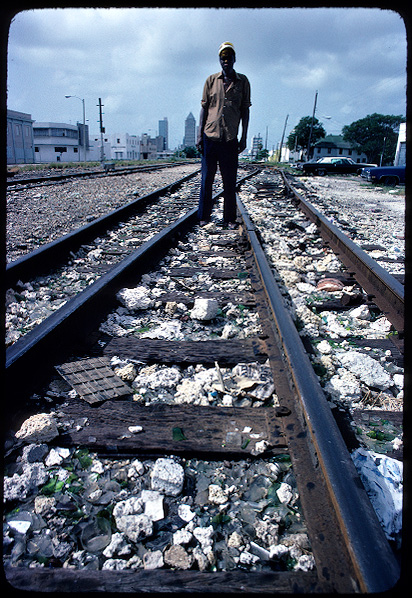

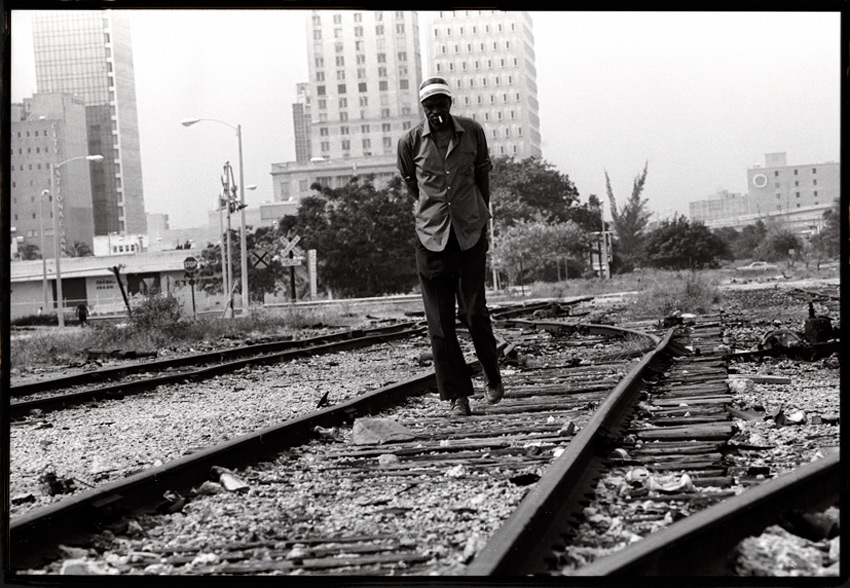

The photos show a haunted man. His jaw juts out, like he's lost teeth. His eyebrows are bushy; once, they probably seemed delicate. A visor throws a shadow across his eyes. A deep scar runs along his left cheekbone. In one, he leans up against the wall of a Winn-Dixie. In another, he walks down railroad tracks, the skyline of Miami rising behind him. He never smiles.

Brennan shot the photos on a Friday night and Saturday morning. Sweet Jimmy smelled of booze and Camel cigarettes. Brennan remembers the last time he saw him. It was in the morning, on the railroad tracks, and he slipped the old fighter 20 bucks. Sweet Jimmy turned and walked off, negotiating the crossties. He never looked back.

"Tell Clay I ain't doing too good," he said.

The paperless trail

We all live parallel lives on paper.

Long after we're gone, the details of our existence will remain part of the public record; in time, they will be all that's known about us, a skeleton of facts, the human whys long decayed. That's what made Sweet Jimmy's disappearance strange. It's hard to disappear. Search engines record everything: our arrests, the amount we paid for our house, the times we've defaulted on a credit card or paid our taxes late. No piece of our past is truly private. The love of a wedding day is public record, as is the hatred of divorce. Public records allow me, in less than two minutes, to learn that Muhammad Ali has a home or office at 8105 Kephart Lane and that his wife has owned a Lexus, license plate LA1, with an AM/FM cassette player and a standard tilt steering wheel. The invasiveness can be scary, but also strangely reassuring. Someday, through these strings of ones and zeroes, people will know we were here. It's impossible not to leave a trail. Finding Jimmy, I was sure, would take a day. Two, tops.

That was six years ago.

I stuck with the search, first while with The Kansas City Star, then at ESPN. Everywhere I turned, I found pain and loss, a procession of wasted lives, people who never fought Ali and, thus, won't ever have someone come looking for them. Did any of these men hang in the pool hall, too, never knowing someone a few feet away shared the same name? A James Robinson born in 1929 was shot a few blocks from the pool hall in 1984, his murderer yelling, "I told you I was gonna kill me a black son of a bitch." A James Robinson died of a gunshot to the head in Overtown in 2007, likely a suicide, but he turned out to be just 54. A Jimmie Robinson was beaten to death under an overpass near the pool hall in 1991. He had an old arrest for being in a park after hours, and his only address was the Camillus House, a local homeless shelter. His date of birth made him too young to have fought Ali in 1961. The Miami medical examiner's office said 227 people have died in Miami since 1980 and never been identified. Any of them could be Sweet Jimmy.

I ran hundreds of searches, through every imaginable database, called every Miami boxing authority still alive. Dundee helped by going through his wealth of boxing sources. The V.A. struck out, as did the military records center and the Social Security office. Current and former law enforcement officers tried to help. The police union sent Sweet Jimmy's picture to old beat cops. The county and city cold case detectives searched. They found no J. Robinsons who were African-American and the right age. The Florida Department of Corrections said it had never had custody of a Jimmy, Jim or James Robinson who fit the description.

Finally, I began to realize that I was looking for Jimmy all wrong. I was looking for him the way I'd look for myself. He'd lived off the grid, managing to go through life and, according to society just out of reach around him, never exist.

It was pointless to look for Sweet Jimmy in my world.

I had to go search in his.

Starting over

The first stop is in Miami Beach at the Fontainebleau Hotel. Elvis and Sinatra stayed here. Bond spied on Goldfinger's card game here. The man I've come to see stands ready to grab my luggage -- an old bellhop, name tag reads Levi. Yes, that's my guy, Levi Forte, an old boxer who fought with Sweet Jimmy. He's been here 44 years, and the tourists whose bags he carries have no idea that he once stood in the ring with champions, just like most folks didn't know that Beau Jack, the old man who shined shoes downstairs, had headlined Madison Square Garden 21 times, more than any fighter before or since.

I show Levi the photograph. He studies the drooping chin, the delicate eyelashes, the wild beard. "That's him," he says. "I haven't seen that guy in I don't know when."

The last time was about 30 years ago, and both men were passing by the famous 5th Street Gym. Levi thought Jimmy would turn and go up the stairs. When he didn't, Levi stopped him.

"You Jimmy Robinson?" he asked.

Jimmy seemed surprised and pleased. The question made him real again, briefly.

"You know me?"

"You fought The Man," Levi said.

The tourists pile out of their cars as I step back into mine. Before I can put it in drive, I hear a knock on the glass. Levi fills my window. He's got a story. One he needs to tell me before I'm gone forever, to prove that he ever existed at all.

"Don't forget," he says. "I was the first guy to go 10 rounds with George Foreman. Dec. 16, 1969."

A line in the water

Next stop: Overtown.

Though it's just a few blocks from the downtown American Airlines Arena, home of the Miami Heat, you can feel the world changing as you turn off Biscayne Boulevard, each street bleaker than the one before, buildings giving way to boarded-up facades giving way to empty lots. People walk toward my car when I stop at traffic lights. Minor laws and small courtesies don't apply; a cop had advised me to run the red lights. People huddle beneath the overpasses. Drug lookouts in white T-shirts eye me warily from corners and the rooftops. Nobody enters Overtown undetected.

It didn't always feel like this. In the '60s, when Sweet Jimmy fought Ali, blacks-only hotels and nightclubs filled each block. The best musicians in the world -- who could play, but not stay, on Miami Beach -- saved their best and wildest sets for Overtown. Everybody came, booked by promoter Clyde Killens: Sam Cooke, Aretha Franklin, Count Basie, B.B. King, John Lee Hooker, everyone. That time and place is as lost as Sweet Jimmy. "You get off of Second Avenue," says Gaspar Gonzalez, a documentary filmmaker who made a movie about Ali's time in Miami, "and there's a hopelessness there. It's an island. There's no sense the world is bigger than that. People are desperate in a way you can't communicate. You're behind God's back."

Driving through the streets, I finger a stack of homemade posters I brought, each with Sweet Jimmy's photo and a local 305 phone number I set up. I explain on them that ESPN is looking for this man but don't include his name. I tape them up around the neighborhood, and I drop them off at all the restaurants, shops and liquor stores. I e-mail them to the secretaries at the local churches; nobody sees or gossips more. If Sweet Jimmy is alive, he's probably in Overtown. Finding a focal point is both satisfying and heartbreaking. All this time, Singer and I didn't know where to look for Jimmy, who never knew anyone was looking.

It's as if he was shipwrecked.

A message in a bottle

Three days after I return home from my first trip to Miami, my phone starts ringing.

The first caller, Melvin Eaton, claims, "I've been knowing old Sweet Jimmy for years."

He says the last time he saw Jimmy was five or six years ago, and that Jimmy never stopped reminding people that he fought Muhammad Ali. He'd shadow box and brag. "That's all he talked about," Melvin tells me. "That's all he talked about. 'I'm the one who fought Ali. I'm the one who should have been the greatest.'"

A few days later, a woman calls. Her name is Brenda. "I see him every day," she says. "He's my friend. He be in Overtown around 12th Street and Second Avenue every day. He be on the street and asks for a dollar for a soda or a beer."

I ask her to go to that corner and put the phone in his hand. "They told me he just walked off," she says later, and I'm not sure whether she really knows Jimmy or just wants to feel like somebody with a mission, with a purpose, even if just for a few thin moments.

These calls point me to the door of Jimmy's world. I go back to Miami. As I'm sitting in the medical examiner's office, waiting to read the files of a few dead James Robinsons, a private investigator suggests checking Camillus House.

It sits on the edge of Overtown, a gateway. Miami has 994 people living on the street, and almost all of them end up here at one time or another. Outside, a man and woman push a stroller toward the shelter door. Another man steps inside holding a baby rattle. I walk up to the front desk, holding a flier. "I'm looking for someone," I tell the lady manning the desk.

Her name is Patricia. As she studies the photo, sadness darkens her face, as though a cloud is passing overhead. She slumps. Every day, unwanted people come through that door, and now, finally, someone has come for one of them -- and it might be too late. "I never forget a face," she says. "He is homeless."

"Is he alive?" I ask.

She shakes her head. She doesn't know.

PART TWO: THE WORLD WHERE NO ONE EXISTS

Ghosts of the pool hall

The pool hall is boarded up, its secrets buried inside. The past is gone. It never happened. No sign of the white father and son who ran a watch repair business here until the '50s, when the son got polio. No sign of Killens, who took over the building; no sign that it once attracted the best sharks passing through Miami; and no sign of Jackie Gleason, who liked to stand atop the tables and sing.

It's the only building left on the block. Once, Ferdie Pacheco, Ali's fight doctor, had an office next door, but it burned in the 1980 riots. Crime took over the avenue. Cops often found themselves at this address. One night, they found a police motorcycle in the back that someone had stolen. As the years passed, fire and the wrecking ball cleared out the rest of the block. The promoter Killens died in 2004, but not before heroin took his son. At the end, Killens sat in his home around the corner with the shades drawn. He stopped listening to music.

The pool hall was condemned in April 2005. Killens' daughter made some poor business decisions and lost the property. It's been empty ever since. Rolling doors, like smaller versions of a garage's, are locked shut. Cinder blocks fill the upstairs windows, where a few apartments used to be, and boards cover the glass painted with the address: 920.

The current owner lets me inside. The tables are gone. The room's painted orange and turquoise, the colors of the Dolphins and nearby Booker T. Washington High. There's a toilet out in the open; the interior walls have been ripped out. The floor's been ripped up. A homeless person lives in the back room, with a basket of clothes and cardboard boxes spread out to form a bed. There's a pile of trash in the corner with a shoe sitting on top. There's a welcome mat.

There is no sign of Jimmy.

Overtown 101

Overtown surrounds the empty pool hall, split north and south by I-95 and east and west by I-395. The concrete canopy is a daily reminder of what the neighborhood used to be, what it's become and why.

Building the interstates in the late '60s forced thousands from their homes, destroyed a vibrant business district and further cut them off from the rest of Miami. Population declined, from 40,000 to where it is today, just more than 10,000. A new kind of economy rules the neighborhood now. A beer or two for a bath. Penicillin or tetracycline might buy you a place to sleep for a night. A crack rock buys just about anything.

The ZIP code, one of the poorest in the country, has more sex offenders than any other in Florida. It's a dumping ground for addicts, pedophiles and the insane. In the shadow of a booming downtown, people live invisible lives. At the corner of NW Third Avenue and 11th Street, I talk to a group gathered beneath I-95. They're looking for cops.

"Police tell us to go home," one guy says, eyeing me suspiciously. "It's martial law in Overtown."

There's one woman in the group. Her arms are disfigured with scars, like she's been in a car wreck. In a way, she has. I'm told later: infections from years of heroin use. She's seen my fliers and asks if I could help her, too. She wants to find out about her daddy. She gives his name. Any little bit of information will help her reconstruct the past, and a past is at the core of our humanity. A story is what makes us real.

Under the overpass, they talk about Sweet Jimmy, whom they haven't seen in a while, and about how people down here just vanish. "Give an emergency contact number," the woman tells her friends. "Let somebody know your name in case you go missing."

They go back to sitting around, their words muffled by the whine and hum of the car tires overhead. They're waiting, for the next hit, the next drink, the next meal, the next green mattress at the Camillus House, waiting for someone to come save them, for their body to end up at the morgue with a tag that says "Remains, Unknown," for the cops to tell them they can't stay here any longer. They're waiting for tomorrow, which will be just like today. The concrete shades them from the hot South Florida sun, and if you stand in just the right spot, sometimes a breeze blows nice and cool on your face.

They're waiting on the breeze.

Lessons of the street

It takes a while, but eventually I make friends in Overtown, and their help opens the neighborhood. Smiles replace stares. The barriers fall away. One morning, local social worker Al Brown and I walk into a barbershop on NW Third Avenue.

"Gentlemen, gentlemen, how are you?" Al says. "I got a gentleman here who's looking for a guy that fought Muhammad Ali. Called him Sweet Jimmy."

A voice calls out from a back room: "Sweet Jimmy's dead."

One of the old barbers introduces himself. "My name's Payne," he says. "I used to cut Jimmy's hair, and the guy in the back used to cut his hair. When he was walking the streets, before he went to the homeless shelter."

"Do you know what happened to him?" I ask.

"He got involved in drugs and walked the streets awhile," Payne says.

"Did he have a job?"

"No job. The street, man. He became an addict, and whoever he knew from the past he would rely on."

Payne knows a guy named Mr. Big, who was friends with Jimmy. He lives down the street in a squat, turquoise building, across from the empty lot where the old Harlem Square club, site of Sam Cooke's famous live album, used to be. Al knocks on Mr. Big's door until he steps out into the sunlight, squints a bit, then tells us he thinks Sweet Jimmy left town.

"How long ago?" Al asks.

"A good while," Big says. "Back in the '80s."

Finally, I am learning some things. I learn most people here didn't really know Jimmy, they just saw Jimmy. They didn't know his last name or his hometown. None actually saw him fight Ali. He moved silently through their lives, as two-dimensional to them as he was to those who read his name in the old boxing records and yellowed newspapers.

I learn there are two groups of old-timers who live here. There are those who held down jobs, like Big and Payne, and there are the hustlers. Both groups knew Jimmy, but as the years passed, he seemed to spend less and less time with the people who kept a foot in the real world. Irby McKnight, a local organizer who's helping me look, moved into the neighborhood the year Jimmy quit fighting.

"When I first met him," he tells me, "he used to be loud and obnoxious, but he was well-dressed. I used to say: 'Where'd this man get these old clothes from?' And people would say: 'That's Sweet Jimmy.' 'You ain't telling me nothing.' 'Oh, you don't know him. He was a boxer and he fought Muhammad Ali.'"

I learn a third thing, too, more slowly than the other two. I learn about the people searching with me. In the beginning, I wondered why they were doing it. I thought about that a lot, especially when I left them in Overtown every day to go back to my fancy hotel, and finally I understood: As long as they help me look, they are a part of my world and not of his. As long as they help, they exist to me.

'He forgets about tomorrow'

We keep looking for people who'd remember, driving every street in Overtown, Mr. Big and Al pointing out the former sites of flop houses and restaurants and nightclubs where Sweet Jimmy spent his days. One by one, they vanished. Wrecking balls took some; riots and fires took others. Sweet Jimmy's world tightened until, finally, only the pool hall was left. He outlived his neighborhood. Old-timers moved or died. Not many folks who knew him are left.

"I tell you who would know," Al says. "Shorty, who used to work at the racetrack."

"Yeah," Big says, "Shorty, he'd know about it. Shorty saw him fight."

"What ever happened to Shorty?" Al says.

"Shorty around," Big says. "I saw him yesterday. He hangs around the corner here by Payne's. Catch him around here in the evening time. Racetrack Shorty."

The next day, we're parked next to an apartment building when Shorty Brown comes outside, a faded hospital bracelet on his arm. The skin hangs loose around his neck.

"Is Sweet Jimmy dead?" I ask.

"If he died, he didn't die here," Shorty says. "He didn't die in this town. If he'd died in this town, you'd know."

Jimmy hustled for money, Shorty explains. Worked his angle, a game with a belt and a pencil, and he was good at it. Shorty is the first of many who try to explain this quaint street hustle, and nobody can do it. Is it real? Is Jimmy real? Did Shorty ever actually see Jimmy? "He used to come to the racetrack and break everybody," he says. "Out at Gulfstream. The last time I saw him, him and Sonny Red screwed with everybody on the racetrack. They put him in jail."

"Who was Sonny Red?" I ask.

"Sonny Red was one of those little hustlers. They go around swindling people. Sweet Jimmy liked that life."

Guys like Shorty, and Jimmy's friend Benny Lane, who called after seeing the flier, paint a picture. The kids made fun of Jimmy's heavy, heel-first walk. He always carried a deck of cards and dealt a mean three-card monte. He laughed at his own jokes when no one else did. He shadow-boxed when the fellas would yell, "Sweet Jimmy!" A guy punched him one night at the pool hall after Jimmy kept on about the man's wife. By then, Jimmy couldn't fight back. "He was always looking to tell a joke or get a joke or say something funny," Benny says. "Get a laugh. A short laugh. Not a long laugh. That's Jimmy."

The years passed. More teeth fell out. He put up his game with the belt and pencil, shedding another thing that made him different from the faceless men and women who wander the Overtown streets. "He wasn't in the best of shape," Benny says. "He drank kinda heavy. And, uh, his mouth was kinda raggedy. Kinda like mine."

Sometimes, Benny and Jimmy would talk. About women, about whatever current events led the news, about home. Now Benny can't remember where Jimmy was from. He thinks Jimmy says he went to school in Kansas City. Sometimes, Jimmy'd pack up and leave for a month or so. He said he had a brother. "He talked about his family," Benny says. "He didn't forget about them."

This picture of Jimmy is the saddest. Not some historical footnote, but Jimmy the man, making it as best as he could. A man who thought about his family and missed his home. Benny tells me that Clyde Killens and a few others who'd made money off Jimmy's fighting watched over him. "Sometimes they cash his check," Benny says, "and give him an allowance because he liked to gamble, and he didn't care. If he gets in a game, he forgets about tomorrow."

As we are about to pull away, Shorty comes running after my car. He's remembered one last thing. "Sweet Jimmy was a disabled vet," he says. "He gets checks from the Army. He gets a check every month. We used to gamble it out of him every month. He said, 'I'm getting 740.' He always told us, 'I get 740.'"

Shorty remembers the check. Benny thinks that Jimmy might have used Killen's address. The current residents remember mail showing up every now and then for a Robinson.

The last letter arrived about a year ago.

Is anything real?

The stories go on as long as you care to listen, and they mirror one another mostly, though the few contradictions make it impossible to know what's fact and what's a cocktail of real memory and decades of street life. One guy who fought Jimmy twice claimed Sweet Jimmy was an impostor, that he didn't fight Ali. I'm as sure as I can be that he's wrong, but I can't be positive. In a way, that's perfect: The possibility exists that the only things people know about the man who called himself Sweet Jimmy are made up. Brenda, who claimed she still sees him, turned out to be high, crazy or running a scam.

All the twists and turns add up to one thing: I didn't get to him in time, and he's probably lost forever.

I keep asking whether anyone actually saw him leave, or saw his dead body, or went to a funeral. Nobody did. One person thinks they remember a program from a funeral, but it's gone, too. It's comforting to those here to imagine him packing up and moving away. The alternative is horrifying: that he died unnoticed, surrounded by people who used to be his friends. That he's in the potter's field down on Galloway Road.

"A lot of people remember him but they can't remember the last time they saw him," says James Hunt, who managed the pool hall from 2002 until it closed in 2005.

Sometimes, Jimmy seems close enough to touch, sitting patiently in the pool hall every day, while Singer and I and everyone else look for him in other places. I can see him hiding in the smoke and the shadows, no past, no future, wearing charity clothes they gave him down at the Camillus House. I see his beard, and I imagine the long forgotten passions that birthed his deep scar. I am close enough to know what his mouth looks like, to see the teeth disappear, and then, he's gone, too, swallowed, a figment of the fractured memory of Overtown. Watching someone be forgotten is like watching them die, and the more people forget, the more it's like he never existed at all. He used to tell some story, they say, but I really wasn't listening.

In those final years, he got quieter, an outsider even here. Regulars shooting pool wouldn't let him in on games. "If he got some money," Hunt says, "he'd play a few games of pool and claim he could have been one of the world's best. When he said things like that, a lot of people ignored him. He always said he could have beat Ali, but he got in the way of the punch."

He didn't like to be called homeless. "I pay rent," he'd say. Nobody remembers where, or if that was even true. Maybe it was a defiant act of pride in a life full of compromises. He walked in the moment the pool hall opened, earlier if Hunt came to clean. Sweet Jimmy would help for a few free games and a soda. He liked Pepsi. People gave him their leftover food. First of the month, he shot a few games of pool, 50 cents a rack, and bought tobacco. He rolled his own cigarettes. Sometimes, Hunt would ask him why. Jimmy'd smile and say, "So I can make 'em as big as I want." The folks who'd loaned him money would line up then, too.

"Jimmy," Hunt would say, "when you get through paying out, you won't have any left."

"No," Jimmy'd say, "but I can make it."

"He always said, 'I can make it,'" Hunt remembers.

Then the pool hall closed.

He never saw Sweet Jimmy again.

PART THREE: WHERE THE HELL DID HE GO?

The thing with feathers

The most important thing in a search isn't a database or contacts or cops. It's hope, and Overtown is methodical in its assault on hope, just as it is unforgiving in its ability to chip away at reality.

Sometimes, people are lost for big reasons; sometimes, they are lost because of a typo.

I am in the Miami library, reading through all the issues of the African-American paper when I see an item that mentions the name of the man originally scheduled to fight Ali Feb. 7, 1961: Willie Gullatt. I know immediately why I've been unable to find him. The white papers, and later books and magazine articles, misspelled his name.

He's in the phone book.

The next afternoon, I am sitting under his carport as Willie, who has just lost a leg to surgery, holds court with his neighbors. He's beloved, with folks crowding around to hear stories and others honking when they drive past. They call him Big Willie. I want to believe that somewhere in America, in a similar fashion, Big Jimmy is telling neighbors about the night he fought Ali. Seeing what his life could have been makes me mourn for him, and makes him seem both closer and further away than ever before.

"I'll be 75 Oct. 6," Willie says. "And still getting me some unda-yonda."

He grins, and his audience falls out.

"I ain't did nothing since I had the operation," he says, "but she gonna get right after a while."

After some small talk, I finally get to ask the question: "What happened that night?"

Money, he says. Promoter Chris Dundee, Angelo's brother, offered Ali $800 and offered Willie only $300. He told 'em where to stick it.

"What did you do instead?"

He smiles, wistfully, remembering an Army duffel bag full of bootleg whiskey. "Got drunk," he says.

Looking back, he's got a lot of regrets. "If I coulda, woulda have left that women and that drinking alone," he says, "I believe I could have had a shot at the championship. But I didn't have the sense I have now. If I'd have had the sense, I'd let that booze alone. Left that damn liquor alone and went out there and had a shot at the championship."

But that's all in the past. Now the triumphs are more modest. The folks in the neighborhood want to throw him a barbecue for Labor Day.

"Sunday?" one asks.

"Every day is Sunday with me," he says.

CSI: Miami

Hope is good.

Hope keeps the city of Miami cold case detectives in business. They sit in a small office with a green door. Files fill the room, each a different victim, people like Sandra Jackson who await closure inside a brown expandable folder, her entire existence reduced to the details of her death: found at empty lot … 3-23-85 … 14:34 … 1255 NW 38th St.

Inside, Andy Arostigui helps me run Robinsons through the system again. Nothing. There's an internal database of information that doesn't rise to the level of public information but might be useful to them one day. Among other things, it tracks nicknames. He gets the officer who manages that system to search Sweet Jimmy. Nothing.

Sitting with Andy and me are two cops from Daly City, Calif., in town to find witnesses for a murder case. I explain that I've been in Miami for a long time looking for a missing boxer. Frank Magnon and Al Cisneros dictate notes back to their home office to help me search another law enforcement database for Jimmy.

"This isn't even a state," says Frank, who's worked down here before. "It's an island of a country. It's like a vapor. They walk in and they're gone."

I fill them in on the search: the fliers and the phone calls, the people in Overtown, the pool hall and barbershops, Mr. Big and Racetrack Shorty.

"His world kept shrinking and shrinking and shrinking," Frank says, "until there was nothing left for him. Some of these guys just drop off the face of the earth."

"And don't want to be found," Al says.

"There was nothing left," Frank says. "He might have decided to just not wake up one day. Sometimes people just say, 'I've had enough.'"

A woman circles the office, pouring the little plastic thimbles of café cubano for the detectives and me. All the homicide guys in the bullpen outside the green door get a midday shot of caffeine, too. Andy finishes his last possible search. Sweet Jimmy's not here. In the beginning, I wanted to sit across from Jimmy and have him tell me about his life. Now, near the end, I just want to find a body.

"I got a feeling," Andy says, "you're gonna find him at the medical examiner's office."

Naming our dead

It's time to meet Sandy Boyd.

We've spoken on the phone many times; she's the cold case detective of the medical examiner's office. Naming the dead is one of our human responsibilities, she believes, and she is tireless in her work.

Her office is like Andy's, terraced in files. These are the people who died alone, who died with nothing in their pockets, who died in horrible fires or in dark waters or, improbably, both: a few they found in burned-out cars buried in silt at the bottom of the canal. These are the people who died seeking a new life, like the body who fell from the wheel well of an airplane, and those who died running from their old ones, like the young suicide victim who broke into a half-built skyscraper and jumped. Scratching out "Remains, Unknown" and writing in a name is a triumph. "One day, I'm gonna solve all these cases," Sandy says. "Little by little, day by day, these cases are gonna get solved. They are someone's loved one."

The folks at the M.E. help me narrow the search. Elise Bobbitt, who runs the indigent burial program, says Sweet Jimmy isn't in one of the city's potter's fields. Sandy figures that there's been only one unidentified African-American body in the right age range found since the pool hall closed. The captain of a river detox boat saw him floating in the Miami River on Dec. 8, 2008 and fished him out. His body's still downstairs, waiting on a name.

Sandy walks me through the morgue, past the autopsy room. "You don't want to see in there," she says.

She explains the logistics of death. When a body comes in, it goes to Cooler 1, which has big stainless steel doors and looks like a restaurant walk-in. The bodies with names and family go to Cooler 2 after autopsy to await funeral home pickup. Cooler 3 is for bodies they're still trying to identify. Cooler 4 provides extra storage space.

She takes me through the doors to another building, opens the door to the Decomposed Autopsy room and the smell of death almost knocks me down -- a combination of really strong blue cheese and old buttermilk. This is where Cooler 5 lives. There's a person on the table. He's got a tag on his left toe. Bleached spots dot his body and his skin is sloughing off in sheets.

Down the hall is Room M164: the bone room. She opens the door. There are rows of metal shelves with cardboard boxes. "These are all unidentified," she says.

Most contain full skeletons. One is from 1957. She opens a box; the skull inside is missing a few teeth. It's waiting on a name. In the back are the boxes from 2004 on.

Could any of them be Jimmy?

Back at her desk, she goes through the computer system. Of the 14 unidentified skeletal remains found since 2005, all can be eliminated, for one reason or another. And we also eliminate a final loose end.

"I can show you the guy from the river," Sandy says.

She digs out the file and hands me a Polaroid. The body is shrouded in blue so only the face is visible, offering the dignity in death he never had in life. His eyes are closed and his nose looks as if it's been broken. He's got a slight overbite and his front two teeth just stick out on his bottom lip. He doesn't have a scar.

Case 2008-03065 is not Sweet Jimmy.

He's not here.

Out there … somewhere

Sweet Jimmy is gone. He didn't leave a record. He doesn't exist on paper, just in the minds of those left in Overtown. He won't even exist there much longer. I walk into James Hunt's home one Saturday morning, and he tells me the news.

Three days earlier, Racetrack Shorty died.

"They're dropping like flies," James says.

Instead of getting closer to finding Jimmy, I'm getting further and further away. The old boxer grows more elusive every day. There is more talk about a brother who supposedly came looking for him. Some people say the brother took Jimmy home. Others say the brother never found him.

I ask everyone the question: Where did he go?

"I think Missouri."

"He might be in Clearwater."

"St. Pete."

"His brother took him to Tampa."

"They say he took him up to Louisiana and he died in Louisiana."

"New Orleans."

"I heard he went to Belle Glade."

"He went to Texas."

"He had an accent that would be more Georgia."

"Georgia, Alabama, I don't know."

"Ohio."

He's everywhere. He's nowhere. He's out there somewhere.

He's got to be.

Doesn't he?

Everything is equivocal

Al Owens lives north of Liberty City, in a house on a corner. He fought Jim Robinson twice. He looks at the photo on the flier.

"That ain't him," he says.

The first time they fought was three months before the Ali bout, the second seven months after. When he got into the ring the second time, he says it was a different guy. He remembers the night because a crowd of hustlers from Second Avenue screamed for Al to kill Jimmy. "They wasn't following him to see him win," he says. "They was following him to see him get his ass whupped."

It was a long, hard fight, and Al says he repressed the memory of it until an autograph collector began writing him letters. Al says he knew Jim Robinson, and he knew Sweet Jimmy, and he claims he saw them together. Then, he says, Jim Robinson quit boxing to join the Army and the street hustler Sweet Jimmy began fighting under his name. "He had the same beard," he says. "He had the scar already. He wore the same visor. The visor was the thing for the guys playing three-card monte."

But Al is a strange character, too, and his memory doesn't stand up to scrutiny. The timeline he lays out is, simply, impossible. He, too, has lost pieces of himself along the way.

I send three photos -- two of a young Jim Robinson in boxing gear and one taken by Brennan -- to a lab in England for scientific comparison. The Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification uses a six-point scale, ranging from "Lends No Support" to "Lends Strong Support." One means they are absolutely not the same person; six means they absolutely are. Their report:

There are numerous morphological and proportional similarities between the man in image 1 and the man in images 2 and 3. There are no apparent morphological or proportional differences which cannot be easily explained by the effects of 20 years of aging, or the differences in camera angle, lighting and resolution; hence, there is nothing to indicate that the man in image 1 is not the same man shown in images 2 and 3. However, these same factors (time, difference in angle, lighting, expression, resolution, etc.) also make it difficult to be more conclusive."

On their scale, they give it a four: lends support.

Even science is equivocal. Nothing in the strange search for Sweet Jimmy is certain. Everything is gauzy, covered in a haze of mights and maybes, his disappearance a mirror held up to his life.

Going home

One stop remains before I step out of Sweet Jimmy's world for the last time and return to mine. On my final Sunday morning in Miami, I show up for my shift volunteering in the Camillus House kitchen. After slicing four hams and dicing a crate of onions, I make my way to the exit. I see a familiar face coming in. Two minutes either way, I'd have missed him.

His name is Shelly. He's 80. He's weathered smooth, like a piece of driftwood, with milky eyes. His rap sheet reaches back to the '70s, with busts from trespassing to auto larceny to drug possession. I met him yesterday, in the street, and he told me he saw Sweet Jimmy leave town. He said he and Jimmy were close, hanging out in the pool hall together. But he seemed out of it, and in a hurry, and standing in the middle of an Overtown street isn't the place for an interview. I thought I'd never see him again.

"Shelly!" I say.

He tries to place me. I remind him we'd spoken yesterday and he seems to remember.

"Do you need anything?" I ask.

"A Pepsi," he says.

I return with two sodas, and we sit in the courtyard, surrounded by other homeless men and women. They are gathered around a radio, listening to gospel and R&B, the old soul hits, staring intently, as if the music has the power to take them away. The tops of some waterfront luxury condos rise high above the shelter, and, hidden behind them is the American Airlines Arena, its outdoor jumbotron flashing messages from another dimension.

"I miss Jimmy," Shelly says.

We talk for an hour and a half. He tells me the story again, and it's the same as he told it yesterday. That's what makes me believe him, because the streets have left his mind fractured, full of images he can't order. I don't think he is capable of remembering a lie.

He says he arrived here 10 years ago: March 15, 1999. He repeats the date over and over. Later, he says he's been here 20 years. I know for sure he was arrested here in 1973, so who knows.

He tells me about his parents, back in Atlanta, who left one day to go to the store and never came back. He tells me about the pool hall regulars trying to hang together after it closed but ending up scattered, about Clyde Killens making sure they all had something to eat and about the last day he ever saw Sweet Jimmy. They were sitting in the pool hall.

"He told me a long time ago," Shelly says, "his brother was gonna come for him, you know. But I didn't know when. Jimmy said he had a brother. I didn't believe it until I saw him. His brother came and got him and took him home. I'm probably the only one who seen him get in the car. Everybody know he left town, but I was there when he got in the car and hauled ass. Shook my hand and every damn thing. Shook my hand. Said, 'I'll see you when I come back.' I never saw him no more."

He points up at the perfect blue sky. "I'll see him again."

A deformed pigeon, large tumors growing off its head, pecks around the concrete patio for crumbs. A crackhead stops throwing himself into a chain-link fence and crawls around under my chair, checking every stray cigarette butt for leftover tobacco. A man who looks too healthy to be here leans back in his chair, closes his eyes and sings along to the music: From the bottom of my heart, it's true … I wish I could take a journey. Shelly sits quietly with the addicts and the sick, all huddled together, unwanted. I don't know if he really saw Jimmy leave, or if his mind's playing tricks, or if he knows his story makes him matter, if only for a moment, to a person who'll buy him a soda and listen to him talk. I believe that, to him, right now, looking for shade in Overtown, it's as true as the day he was born. Shelly takes a sip of his Pepsi and thinks about all the people who've come and gone.

"They disappear like the wind," he says.

Epilogue

The journey ends where it began. Six years after he first called, Stephen Singer leads me back through his office until we're standing in front of what he calls the masterpiece: two large frames 6 feet across containing a collage of photos, programs, ticket stubs and, of course, 49 signatures. There's an engraved plaque: "Jim Robinson's whereabouts unknown … autograph missing."

He's no longer searching for Jimmy. "I moved on," he says. "I haven't really thought about it for a couple of years. I'm way past that. I've got real work to do."

I find myself wondering why I haven't moved on.

It's easy to believe the journey of Sweet Jimmy is unique. It's not. Singer's collection is a reminder of how a boxing life often goes completely off track.

Tunney Hunsaker, the first opponent, spent nine days in a coma after a bout.

Trevor Berbick, the final opponent, was beat to death with a steel pipe.

Herb Siler went to prison for shooting his girlfriend.

Tony Esperti went to prison for a Mafia hit in a Miami Beach nightclub.

Alfredo Evangelista went to prison in Spain.

Alejandro Lavorante died from injuries sustained in the ring.

Sonny Banks did, too.

Jerry Quarry died broke, his mind scrambled from dementia pugilistica.

Jimmy Ellis suffered from it, too.

Rudi Lubbers turned into a drunk and joined a carnival.

Buster Mathis blew up to 550 pounds and died of a heart attack at 52.

George Chuvalo lost three sons to heroin overdoses; his wife killed herself after the second son's death.

Oscar Bonavena was shot through the heart with a high-powered rifle outside a Reno whorehouse.

Cleveland Williams was killed in a hit-and-run.

Zora Folley died mysteriously in a motel swimming pool.

Sonny Liston died of a drug overdose in Las Vegas. Many still believe the Mafia killed him.

"That's the saddest one," I say to Singer.

"They're all sad," he says. "They're all sad in their own way."

Even finding Sweet Jimmy isn't certain to provide any answers about his life; he might not remember he ever fought at all. Many old fighters end their lives stripped of their memories. The night Jimmy fought Ali, the main event was a light heavyweight title fight between Harold Johnson and Jesse Bowdry. Today, Johnson lives in a Philadelphia V.A. nursing home and has good days and bad days. His memory is going. Bowdry's wife answers the phone in their St. Louis home. "He's not gonna remember," she says. "He has dementia."

Even Ali is a prisoner in his own body, a ghost like Sweet Jimmy, lost in a different way. He paid a price for his fame, just as the men who fought him paid a price for their brush with it. Nothing is free. Confronting the wreckage reminds me of an old magazine story, written by Davis Miller. There's a haunting moment, in 1989 when things were turning bad. Ali stands at the window of his suite on the 24th floor of the Mirage Hotel in Las Vegas. His once booming voice comes out a whisper.

"Look at this place," he says. "This big hotel, this town. It's dust, all dust. Don't none of it mean nothin'. It's all only dust."

A fighter jet lands at an Air Force base out on the desert. Ali watches it through the glass, the lights on the strip so bright it seems like they'll burn forever.

"Go up in an airplane," he says. "Go high enough, and it's like we don't even exist."

Join the conversation about "Shadow Boxing."

Wright Thompson is a senior writer for ESPN.com and ESPN The Magazine. He can be reached at wrightespn@gmail.com.