|

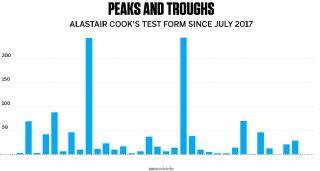

We need to talk about Alastair Cook. We know he is England's most prolific batsman. We know his place in England's Test history is assured. We even know he was the top-scorer in England's top six at Trent Bridge on Sunday and that, aged 33, there should be some miles left in the tank. But Cook is starting to look like the gym subscription you forget to cancel; the mobile phone contract that ties you in long after the screen is broken; the much-loved family pet whose next trip to the vet may not involve a return journey. It's starting to become hard to deny that he is in an inexorable decline. That he is being retained long after England should have moved on. Wait there, you might say. It's only a few Tests since he scored a double-century in Australia. And, not long before that, he scored another double against West Indies. And, even in this game, he has taken an outstanding slip catch. All that's true. But between those double-centuries - a five-Test span which saw the Ashes decided - he averaged just 14.40. And, since the double in Melbourne - seven-and-a-half Tests that saw England defeated by New Zealand and held to a draw by Pakistan - he is averaging just 19.38. And, while it's true he held a fine catch in the first innings, he missed a pretty straightforward one in the second and has taken around 70 percent of chances since the start of 2016. That's about 10 percent below the rate of South Africa and Australia in the slips over the same period. What we see now is an opening batsman uncertain where his off stump is. An opening batsman uncertain whether to play or leave. Who, in going straight back rather than back and across, seems to be stretching to play deliveries only slightly outside off stump. An opening batsmen who is stuck in the crease and often looks hurried. And bowling attacks who are on to him and know exactly where to bowl. Those double-centuries have something in common. They were made on slow surfaces providing the bowlers little assistance. The first one, against West Indies in August 2017, was also made against a pink ball that refused to swing while the second one, at Melbourne, was on a pitch so absent of assistance for bowlers that it was subsequently rated "poor" by the ICC. That's a pattern that extends a long way further back. If we reflect on Cook's most recent Test centuries, we find evidence that suggests he has become something approaching the ultimate flat-track bully. Before those two doubles, we have to go back to November 2016 for a Cook century. That one, in Rajkot, was made on a surface so slow and flat that England passed 500 in their first innings - he was one of four England players to make a century in the drawn match - while the previous one (in July 2016) came at Old Trafford on a surface upon which Joe Root made a career-best 235 and England declared just short of 600. Before that, he made another double against Pakistan in Abu Dhabi (in October 2015) on a surface on which England again declared just short of 600. You have to go back a long, long way to find a century made in demanding batting conditions or even on a quick pitch. Those vast scores distort Cook's record. For example, he finished the Ashes with a series average of 47, which sounds pretty good. But he passed 50 only once in the series - in the unbeaten 244 - and the rest of the time contributed just 132 in eight innings at an average of 16.50. He has long since stopped offering any sense of assurance at the top of the order. Instead, he is doing just enough to preserve his place but nowhere near enough to shape the course of a game except on the very flattest surfaces. Besides, if you give any good county batsman enough opportunities, they will register the occasional high score. It's consistency that marks out the really good players.  England can't afford Cook's failures, either. Their middle order, for all its entertainment value, needs protecting from the ball at its newest and the bowlers at their freshest. They have already pushed Joe Root up to No. 3 and Ollie Pope - who had never come to the crease in a first-class innings before the 20th over - up to No. 4. On Test debut he was in before the ball was 10 overs old. Then you have Jonny Bairstow, whose reaction to every situation appears to be to try to hit the ball harder, in at No. 5, the aggressive Ben Stokes at No. 6, and a man at No. 7 who is 23 Tests into his career but has yet to make a century. All the recipes for collapse are there. Which is why they have now lost all ten wickets in a single session three times in the last two years. Between 1936 and 2016 that never happened. England need Cook to provide the old-fashioned grit to complement the rest of the team's new-world flair. There are a couple of factors strongly in Cook's favour. The first is that Ed Smith, the national selector, is clearly a believer in his strengths. Smith was, after all, still advocating the retention of Cook in England's ODI team when he was sacked just ahead of the 2015 World Cup. But Cook's greatest asset at present is not so much his record as the record of those vying to replace him. For all his current problems, with Keaton Jennings averaging 23.76 after nine-and-a-half Tests and 22 in three-and-a-half since his recall, Cook is not even the most worrying opener in the side. In a perfect world - a world where the domestic structure is designed to develop Test players - there should be a queue of candidates knocking at the door to replace both Cook and Jennings. In reality, however, we know England have tried a dozen options to partner Cook without success. There aren't too many options left. Haseeb Hameed, who left the India tour at the end of 2016 looking every inch a Test batsman, has not made a century since. Indeed, he's averaged just 20.07 in first-class cricket since with three half-centuries in 44 innings. Ben Duckett, who was good enough to score more than 1,300 runs in the 2016 season, is averaging 26.78 in Division Two this year. And while Nick Gubbins is averaging almost 60 in the Championship season, he is playing only his fourth game having suffered injury and has a modest record against spin bowling. Bearing in mind England's winter plans - tours to Sri Lanka and the Caribbean - that does him few favours.  Then there's Rory Burns. He has almost 881 Division One runs this season - that's 181 more than anyone else in the division - at an average of 67.76 (almost 30 more than Cook for Essex) and recently won praise from Dale Steyn for his temperament and technique. He is not an especially pretty batsman - he has an odd habit of peering to midwicket just ahead of delivery as if the fielder has just whispered something appalling about him - but he is effective, hungry, bright and determined. England's batting collapses are none too pretty, either.

Then there's Rory Burns. He has almost 881 Division One runs this season - that's 181 more than anyone else in the division - at an average of 67.76 (almost 30 more than Cook for Essex) and recently won praise from Dale Steyn for his temperament and technique. He is not an especially pretty batsman - he has an odd habit of peering to midwicket just ahead of delivery as if the fielder has just whispered something appalling about him - but he is effective, hungry, bright and determined. England's batting collapses are none too pretty, either.

It might not help his opening partners that Cook is at the other end. With his own struggles to worry about, he is in no position to take the pressure off them by either hitting a bowler off their length or even giving the sense of permanence that might dispirit them. Instead, the novice openers see the scoreboard going nowhere and bowlers allowed to settle into spells. There's no slipstream to benefit from. Cook has had a great career. And he is going to have every opportunity to bat for a day or two in the second innings of this game. But all the evidence suggests the old lion is limping and the hyenas are circling.

|