|

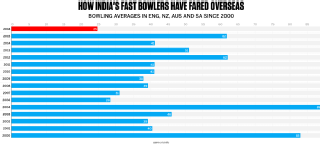

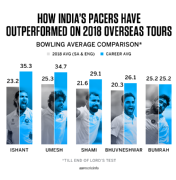

In five Tests in South Africa and England this year, India's fast bowlers have collectively taken 69 wickets at an average of 24.75. All five frontline quicks India have played - Mohammed Shami, Ishant Sharma, Jasprit Bumrah, Bhuvneshwar Kumar and Umesh Yadav - average below 26 across the two tours, and have strike rates of less than 50. These are rare and spectacular numbers. We need to go back 12 years - to 2006 - for the last year in which India's quicks averaged less than 30 as a collective in Australia, England, New Zealand and South Africa, and go back another decade, to 1996, for the next-most-recent instance. It doesn't happen often.  Why then is no one heralding the birth of a new fast-bowling power in world cricket? In one word, context. India's fast bowlers have achieved these numbers in conditions unusually loaded in their favour. Ishant's average across these two tours, 23.20, is on a different planet to his career average of 35.32. He's an improved bowler now, sure, but not that far improved. He doesn't bowl rank bad balls, but he still bowls spells where he's a foot too short and a foot too wide of off stump to really test top batsmen. Shami can look deadly when he lands the ball in the fourth-stump channel with seam bolt upright, but he still bowls spells interspersed with long-hops and leg-stump half-volleys. In the same conditions where Ishant has averaged 23.20 and Shami 21.61, should it surprise India at all that their batsmen have struggled terribly? That too against two of the world's best fast-bowling attacks in their own backyards?  Think back to the first Test of this cycle, in Cape Town, and the first session of the second morning. India, three down early, played that session about as well as they could have, losing just the one wicket in green, seaming conditions against a four-man pace attack comparable to the best of West Indies' fast-bowling packs from the 1980s: Vernon Philander, Dale Steyn, Morne Morkel and Kagiso Rabada. Only 48 runs came in that session of 25 overs, and it was hard to tell how Cheteshwar Pujara and Rohit Sharma, who batted through the bulk of it, could have scored any more. Over after over, both did most things right - they played with a straight bat and soft hands, and were vigilant outside off stump - but even so, it seemed a matter of time before an unplayable ball or a small error of judgment would arrive. The conditions increased the frequency of the former and magnified the consequences of the latter. Pretty much every innings India have batted in on these two tours has been similar, give or take a couple of degrees of difficulty. The cumulative effect on this batting line-up cannot be overstated. Form can be self-perpetuating, whether it's good form as in the case of Virat Kohli or bad as in the case of every other India batsman. You can trust in your methods, as Pujara has done, soaking up pressure and avoiding any risk whatsoever, and average 14.75. Or you can change your game and go after balls you might ordinarily leave, as Ajinkya Rahane has done, and average 17.50. Before the series began, Pujara's form was a major concern, with the No. 3 having endured a terrible season with Yorkshire. "I feel he is one innings away [from a big score]," India coach Ravi Shastri said, when asked about this. "He needs to spend time at the crease. If he gets one 60-70 under his belt, he will be a different player altogether." A player being "one innings away" from regaining form is one of cricket's oldest cliches, but it's also true - a good score calms the mind, fills you with confidence, and gets your footwork and bat-swing back in rhythm. That one innings, however, is exceedingly difficult to come by in conditions like those at Edgbaston or the damp, overcast second day at Lord's, where, according to CricViz's data, the ball swung and seamed twice as much as the global average. In such conditions, with play constantly interrupted by rain, and against one of the masters of swing and seam in James Anderson, 107 was just about par as a first-innings total. With a bit more luck and a couple of instances of better judgment - Pujara's run-out in particular - they might have stretched it to 150. In extremely bowler-friendly conditions, the margin between failure and success can be that small. Go back to India's only win on this cycle of tours, and M Vijay's second-innings masterclass on a Johannesburg pitch of shockingly inconsistent bounce. It yielded him all of 25 runs. Imagine batting with utmost vigilance for more than three hours, leaving painstakingly outside off stump, taking a battering from rising balls, and ending up with just 25.  A Test batsman can expect to be challenged by such conditions occasionally, once or twice a year perhaps. This year, India's top order has had to endure them week in and week out. There have been no cheap 25s, forget cheap fifties and hundreds. In the era of Rahul Dravid, Sachin Tendulkar and VVS Laxman, India never went through back-to-back tours in conditions as difficult as this, with New Zealand in 2002-03 perhaps the only comparable single tour.

A Test batsman can expect to be challenged by such conditions occasionally, once or twice a year perhaps. This year, India's top order has had to endure them week in and week out. There have been no cheap 25s, forget cheap fifties and hundreds. In the era of Rahul Dravid, Sachin Tendulkar and VVS Laxman, India never went through back-to-back tours in conditions as difficult as this, with New Zealand in 2002-03 perhaps the only comparable single tour.

Could India have been better prepared for both South Africa and England? Definitely. Could their batsmen do with a little more mental security, knowing that they aren't one failure away from being dropped? Undoubtedly. But neither of those issues is the cause of their struggle as a batting unit on these two tours, which is largely down to the conditions they've faced. It's not as if the South African and English batsmen have prospered. Both teams have trusted in the superiority of their pace attacks to win them Test matches, and been willing to sacrifice the records of their own batsmen. Only one of England's top-order batsmen - Jonny Bairstow - has averaged more than 40 in this series, and only one South African batsman - Dean Elgar - did so in their home series against India in January. It's not dissimilar to what India did when South Africa came visiting in 2015-16, preparing square turners to weaponise their own spinners and negate an opposition line-up that included Hashim Amla, AB de Villiers and Faf du Plessis. "I don't mind compromising on [batsmen's] averages as long as we are winning Test matches," Kohli said then. "I think that's our main concern, we are not playing for records, we are not playing for numbers or averages ... If you don't take 20 wickets, you can have an average of 55, it doesn't matter." India have gone back to preparing more sporting pitches since then - with Pune 2017 a notable exception - but the rest of the world seems to have absorbed quite a lesson from that 2015-16 series. As we've seen from India's two most recent overseas tours, and South Africa's just-concluded visit to Sri Lanka, this is an era of exaggerated home advantage. The overseas records of a number of fine batsmen are simply collateral damage.

|