|

The sports betting landscape in America shifted forever on a Monday morning in May, when the U.S. Supreme Court released a game-changing ruling that put the nation on a path toward widespread legal sports betting. Shortly after 10 a.m. ET, on May 14, the Supreme Court struck down the 1992 Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act, which for 26 years had limited legal sports betting to primarily Las Vegas. The interest in the decision was remarkable. SCOTUS had already decided cases on terrorism, immigration and human rights violations in the term, but none of those hot-button issues generated near the public interest that the New Jersey sports betting case did. At SCOTUSBlog.com, the preeminent site covering the Supreme Court, the post announcing the sports betting decision drew nearly double the page views of any other post since last June. As soon as the ruling was released, social media lit up with a mix of excitement and concern. Stock prices for domestic and international bookmaking companies surged, and a New Jersey racetrack announced that it was hustling to begin taking sports bets within weeks. Sports betting had made national news -- for something other than a controversy. Even Golden State coach Steve Kerr took notice, joking before Game 1 of the Western Conference Finals that he was "taking the Warriors +1.5." "I read that whole story about gambling this morning," Kerr said with a smirk, "so now I guess I'm allowed to announce my picks." To be clear: Americans were betting hundreds of billions of dollars on sports before the ruling and will continue doing so moving forward. Perhaps the most noticeable impact the Supreme Court ruling has had is that America now may be a little more comfortable talking about sports betting. It's been a long process to get to this point. Stiff opposition from the influential sports leagues, ties to the mob and decades of scandals tattooed a stigma on sports betting that other forms of gambling never had to overcome. On top of religious objections and concerns of addiction, sports betting was -- and continues to be -- viewed as a threat to the integrity of American sports. There has been sudden sea change, though: In just the past five years, society's -- and the sports leagues' -- acceptance of sports betting has markedly increased. A myriad of factors brought us to this revolutionary point in American gambling history: Daily fantasy rose to prominence, the media embraced point-spread talk and the leagues, with the help of some new forward-thinking commissioners, softened their opposition. It all culminated last week with a press conference that had the commissioner of the NBA sitting side-by-side with the CEO of one of the largest legal bookmakers in the U.S. to announce a partnership. The times, they are a-changing, and whether or not America is ready, legal sports betting is now mainstream. How did we get here?

Fantasy football: More than "just nerds"Fantasy football didn't really start to annoy the NFL until the 1990s brought the internet into the game. Organizing fantasy leagues, holding drafts and keeping score became more efficient, but player notes and injury updates still weren't readily available. This led to ambitious fantasy owners resorting to calling public relations offices for teams, asking for any details about injuries and player statuses. "The leagues just hated us," said Greg Ambrosius, a longtime fantasy sports advocate and former chairman and president of the Fantasy Sports Trade Association. "We were just nerds. Forget the fact that we were fans, they considered us a niche audience of stat geeks." Despite the NFL's reticence, media coverage of fantasy sports increased in the 1990s. In 1995, Ambrosius joined Starwave, ESPN.com's predecessor, as the site's first fantasy sports writer. CBS' SportsLine.com and Yahoo Sports also revved up fantasy coverage. The NFL remained hesitant. Network partners were discouraged from discussing fantasy during broadcasts, until an enterprising executive arrived at the NFL. "Internet fantasy was only a few years old," recalled Chris Russo, who was hired in 1999 as NFL senior vice president and put in charge of new media, including the league's website, NFL.com. "I think there was not a huge understanding of what it was, and maybe there were concerns about whether it would be right for the fans or could it be construed as gambling. There were a lot of questions." Russo, a casual fantasy player, set out to answer those questions and initiated a study on fantasy sports. He found fantasy players watched more games than average fans. Not surprisingly, this resonated with the league. "It was like a lightbulb went on," remembered Peter Schoenke, a fantasy pioneer and president and co-founder of RotoWire.com. "The NFL completely switched gears from distancing itself from fantasy to embracing it." NFL players started appearing in commercials for the league's fantasy game. The NFLPA began sponsoring fantasy conferences. Suddenly, the fantasy nerds and stat geeks were identified as diehard fans, leading NFL.com to launch its first fantasy game.  Roughly 10 years later, daily fantasy sports -- led by DraftKings and FanDuel -- came along and disrupted the status quo. To many, DFS looked a lot more like sports betting than traditional season-long fantasy games among buddies. The NFL noticed the difference as well. "Season-long fantasy ... it's for fun," NFL commissioner Roger Goodell said during a 2015 fan forum in Minneapolis, adding that "Daily fantasy's taken a little different approach." While the NFL expressed concerns, it didn't restrict owners and teams from getting a piece of the pie. Jerry Jones and Robert Kraft -- the prominent owners of the Dallas Cowboys and New England Patriots, respectively -- invested in DraftKings. All but a few teams did marketing agreements with DFS companies, and high-profile players began promoting the games on social media. The NBA and Major League Baseball, at the league level, also took equity positions in FanDuel and DraftKings, respectively, giving the growing startups a boost of legitimacy. But trouble was around the corner. In the lead-up to the 2015 football season, DraftKings and FanDuel bombarded airwaves with advertising. At the peak of the marketing blitz -- a three-week stretch from August to September 2015 -- an ad for either DraftKings of FanDuel ran on national TV every 90 seconds. Politicians began to squawk about the rampant advertising, and then all hell broke loose. In October, a DraftKings employee, who had just won $350,000 playing on FanDuel, erroneously published data perceived to be advantageous before the week's games had ended. Players were concerned that he had access to information that was not public and used it to set his lineups. Accusations of insider trading and cheating followed. An independent investigation later cleared the employee of any wrong-doing, but a torch had been lit. Federal and state inquiries were launched, and dozens of lawsuits were filed, including some that are still active today. DFS survived it all, but industry growth subsided, and the major players are now shifting gears and becoming sports betting operators. FanDuel was recently purchased by European bookmaker Paddy Power Betfair and is running the sportsbook at the Meadowlands Racetrack in New Jersey. DraftKings also is aggressively moving into the sports betting space and last week became the first company to launch a mobile sportsbook in New Jersey. "In a strange way," said Russo, now managing director of global investment bank Houlihan Lokey, "all of the controversy around daily fantasy -- Is it a game of skill? Is it gambling? -- may have been the bridge to sports gambling." Regardless of the missteps and shakier legal footing of DFS, one thing is clear: sports fans playing fantasy sports (daily or season-long) are more engaged fans. And DFS is a perfect fit for a younger generation, which wants quick payouts available from their phone. "The media also has had big impact," Russo added, "in part because there was such intense coverage of the fantasy debate. And that has led to the next question, which is if daily fantasy is OK, why not sports betting? Is that really that much of a jump?"

Sports mediaThink you've heard all Lee Corso's best catchphrases? Not so fast, my friend. Behind the scenes, during early production meetings for "College GameDay," the charismatic coach also had a go-to line that may be his most poignant: "All people care about is who is going to win and by how many." "That's it," said vice president of ESPN college sports and longtime GameDay producer Lee Fitting of Corso's straightforward take on the show's audience. "And if you're ignorant to that fact, you're missing the boat completely." Right now, the mainstream media is all aboard the sports-betting boat, but it's been a long and bumpy voyage dating back to the 70s.  Hall of fame sportscaster Brent Musburger points back to 1976, when then-NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle decided to add bookmaker Jimmy "The Greek" Snyder on CBS's iconic Sunday morning preview show, "The NFL Today." "The Greek really brought it more mainstream," recalled Musburger, now living in Las Vegas, where he broadcasts from a studio in the middle of a casino for the Vegas Stats & Information Network (VSiN). Musburger and the Greek were asked not to mention the exact point spread during the show, but they worked around it, setting the stage for decades of veiled gambling references during game broadcasts. The final drive of Super Bowl XXIX between the San Francisco 49ers and San Diego Chargers is a prime example. Then-ABC broadcaster Al Michaels was on the call. The 49ers, who were 18.5-point favorites, had the game wrapped up, leading 49-26 late in the fourth quarter. Starting inside San Diego's own 10-yard line, quarterback Stan Humphries drove the Chargers into San Francisco territory, connecting with Tony Martin for a first down to the 49ers' 43-yard line with around 40 seconds left. "That will make a few people around this great land of ours move to the forward portion of the couch," Michaels quipped. "You better believe it." A touchdown would be meaningless to the outcome, but would have covered the spread. In the final seconds, Humphries lofted a pass toward the corner of the end zone. "Hearts beating all over the land ..." said Michaels, slyly noting nervous bettors sweating the final plays. "Incomplete." "There were a couple of us, Al Michaels and myself, who were never really shy about it," Musburger said of his knack of referencing the betting impact late in games. "I think we realized that you can hold an audience with it." The wink-and-nod gambling references chipped away at America's fear of sports betting, but it was a slow process. Musburger said potential blowback from the sports leagues kept mainstream media, including ESPN, from embracing sports betting sooner. ESPN didn't start running NFL point spreads on the SportsCenter Bottom Line until 2000, at first restricting them to a 12-hour overnight window from late Saturday until about 15 minutes before "NFL Countdown" started Sunday morning. The reins began to loosen later in the decade. In 2008, ESPN.com began a regular gambling column and podcast "Behind the Bets," and, in 2014, launched "Chalk," the site's vertical dedicated to gambling. Around the same time, leading into the 2014 college football season, Fitting told the GameDay cast that they were going to "stick our neck out there a little bit" and talk more openly about point spreads, odds and sports betting overall, something long frowned upon by the NCAA. "Too often, you run into people and they're scared, like gambling is a bad word," said Fitting. "You can't be scared of it. Our motto has been to be fearless, but not reckless when talking gambling." Lines and over/under totals for games started being included in more graphics, not to be referenced with every matchup, but more so as just an added piece of content. Chris Fallica, a seasoned handicapper affectionately known as "Bear," was infused more on camera, albeit to the side of the show's main set, where gambling probably belongs in the big picture of college sports -- it's a part of the story, but not the main show. "I do think that everyone will need to find the right way of highlighting [betting], while not letting it overtake the pureness and the fun of the game," Russo told ESPN. "I don't think anyone has any answers on that yet. "I think the leagues will have to balance that with the broadcasters," he added. "It's great to have engagement, but if you lose a bunch of money then you're not so engaged anymore."  It's a line that the traditional mainstream media outlets that own rights must negotiate moving forward. The CBS, Fox, NBC and ESPNs of the world need to decide how to serve their pure sports fan audiences, while also engaging a growing demographic of viewers who are more interested in "who is going to win and by how much" -- and at the same time avoid upsetting their sports league partners. Some newer outlets, like Musburger's VSiN, and The Chernin Group's Action Network are flipping the model on its head. They've chosen to focus on the sports bettor more than the sports fan. And they were going to launch regardless of SCOTUS' ruling -- though it certainly didn't hurt. The Action Network combines established fantasy and sports betting analytic sites with an app tailored for bettors and launched last fall, under the direction of former ESPN executive Chad Millman. "[We're] really catering to both the fantasy and betting markets that already exist in the U.S.," Mike Kerns, president of digital for The Chernin Group, said in a phone interview just days before the Supreme Court ruling. "We've studied it: The United States already has the largest per capita sports betting society in the world, even though it's illegal everywhere outside of Las Vegas." VSiN operates out of a broadcast studio that sits in middle of a Las Vegas casino, adjacent to the 24-hour South Point sportsbook. The company is expanding outside of Nevada, too, and is now contributing regular print content to the New York Post. "Even if the Supreme Court ruled against New Jersey," added Brian Musburger, Brent's nephew and co-founder and chairman of VSiN, "it [wouldn't] stop sports betting in the United States. People are finding a way to put a little money on sports events, and that's not going to change." A rise in recent years of gambling-centric stories hasn't hurt, ranging from Leicester City winning the 2015-16 Premier League title at 5,000-1 odds to Floyd Mayweather attempting to bet on his fight against Conor McGregor, to the Philadelphia Eagles wearing dog masks throughout their underdog run to the Super Bowl LII title. "I think that everyone became aware of the nuanced ways that you could talk about sports betting that connected the storytelling to the conversation in ways that were more than a wink and a nod," Millman said. "It connected it to the analytics, the stats and the alternative ways to examine a game, which happened to be the ways that people in Las Vegas, professional sports bettors have been doing it for a long time."

Sports leagues change their tune on bettingIt was an awkward moment inside the Supreme Court, towards the end of oral arguments in the New Jersey sports betting case. Chief Justice John Roberts seemed dumbfounded by U.S. Deputy Solicitor General Jeffrey Wall, who was arguing on the side of the NCAA and major professional sports leagues. "Well, is that serious?" Roberts asked Wall. "You have no problem if there's no prohibition at all and anybody can engage in any kind of gambling they want, a 12-year-old can come into the casino and -- you're not serious about that." Wall paused before responding: "I -- I'm very serious about it, Mr. Chief Justice." The entire courtroom seemed to squirm in their seats, and there were a few hushed, but audible gasps, as if underdog New Jersey had just scored the decisive blow. Four months later, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of New Jersey, 6-3, handing the NCAA and major professional sports leagues a jarring defeat on an issue that for decades they had decried as their mortal enemy -- sports betting. In 2012 deposition testimony, Goodell said gambling was the No. 1 threat to the integrity of the game. Then-MLB commissioner Bud Selig said sports betting was "evil," and the NHL's Gary Bettman and NCAA president Mark Emmert echoed those sentiments in an effort to stop New Jersey. At that point, the leagues' opposition to legalizing sports betting appeared united and unwavering, but, behind the scenes, the NBA was plotting change. In 2006, then-NBA deputy commission Adam Silver began to question if forcing the bulk of the billions of dollars wagered on sports in the U.S. into a black market was the most pragmatic approach. He witnessed in person how jurisdictions in Europe and Asia dealt with sports betting and started to listen to pitches from international gaming companies.  Thoughts of pivoting the NBA's position were halted in 2007 when the Tim Donaghy scandal was revealed. For gambling, this was as ugly as it gets: a referee convicted of providing information to gamblers and admitting to betting on basketball himself, including games he officiated. The NBA never saw it coming. The safeguards the league had in place didn't detect the bets by Donaghy or his co-conspirators, because evidence showed that they were made mostly with local and offshore bookmakers. Gaining more transparent access to the largest betting markets became a priority for Silver. The best way to accomplish that, he thought, was to bring sports betting out into the open. "[I] believe that sports betting should be brought out of the underground and into the sunlight where it can be appropriately monitored and regulated," Silver wrote in an op-ed in The New York Times that was posted online mid-evening Nov. 13, 2014 and ran the following day in the print edition under the headline, "Legalize Sports Betting." It was a stunning icebreaker on a taboo topic for the sports leagues. Months later, new Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred said publicly "fresh consideration" should be given to legalizing betting. And within the next two years, the NHL and NFL allowed franchises to be placed in Las Vegas, America's sports betting capital. At least to a degree, the leagues' doomsday outlook at sports betting legalization began to fade. "I do think Adam Silver's New York Times op-ed was a watershed moment for sports betting," said Andrew Brandt, former vice president of the Green Bay Packers. "There have been mixed messages for some time, with leagues espousing integrity yet realizing the reality of the fan-engagement possibilities of sports betting. But here was the commissioner of the second-most popular sports league taking it upon himself to support bringing gambling out into the open. That gave credibility to the stance and opened the door for investment into DFS companies, less taboo in talking about it, and eventual -- though gradual -- similar sentiments from other commissioners."

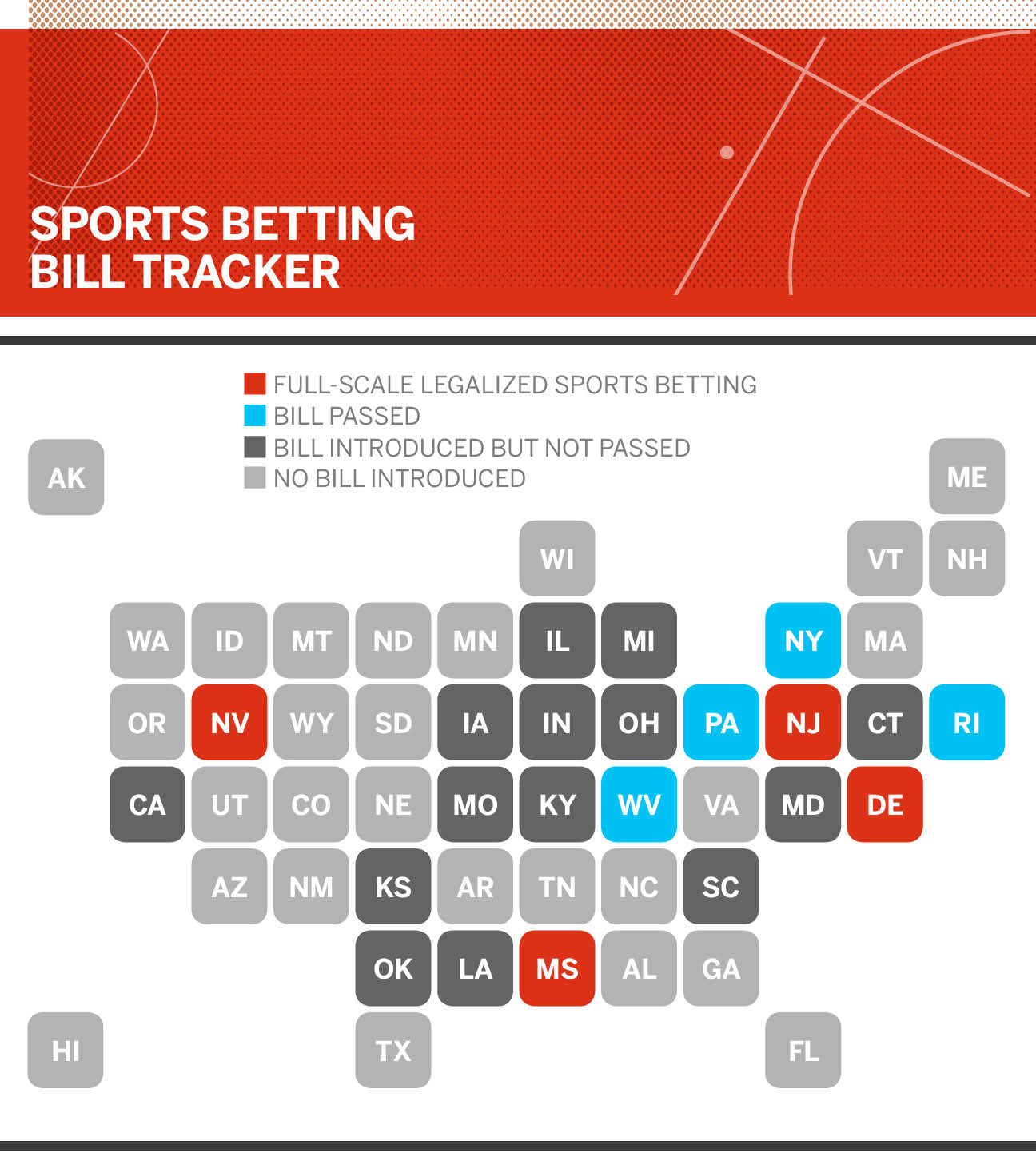

Just as there will always be human competition, there also will be people to bet on it -- legal or not. In fact, gambling is one of mankind's oldest activities. Evidence indicates our ancestors, shortly after developing opposable thumbs, made dice out of animal bones to play games. Babylonian soldiers held chariot races, and by the 8th century B.C., laws addressing gambling were in place in Ancient Rome. Today, the American Gaming Association estimates $150 billion is wagered on sports annually in the U.S., with only a tiny percentage taking place in Nevada's regulated market. Silver has cited estimates as high as $400 billion in annual sports wagers, or nearly double Apple's annual revenue. No one really knows how much we're betting, but one thing is clear about America's sports betting affinity -- it's never going to stop and now it has a legal stamp of approval.  "Americans have never been of one mind about gambling," Supreme Court justice Samuel Alito wrote in the first sentence of his opinion for the New Jersey case, "and attitudes have swung back and forth." As Alito noted, how far society has evolved on sports betting remains up for debate. A poll conducted in May by the National Research Group of more than 1,000 Americans found 60 percent now approve of sports gambling, a dramatic shift compared to results of similar polls conducted 30 years ago when 56 percent disapproved. However, passionate opposition, with concerns over potential spikes in addiction, game corruption and predatory gambling practices, continue to resist. Still, states are moving forward quickly. Since the May 14 decision, Delaware, New Jersey and Mississippi have begun taking sports bets, and West Virginia is aiming to be up and running by the start of the NFL season. New York, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island also have sports betting laws in place, and 14 additional states have introduced legislation to address the issue. It's happening fast, whether America accepts it or not.

|