|

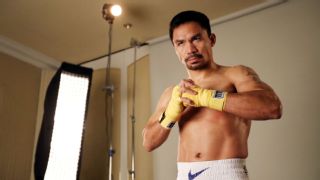

Many already realize that it has actually been almost a decade since Manny Pacquiao won by a stoppage. Now, he matches up against Lucas Matthysse; a younger, hungry pugilist whose last two triumphs didn't even make it to the judges' scorecards. Naturally, many Filipino fans are concerned that the People's Champion may have finally gotten himself into a situation that may be detrimental to the status of the legend he is slowly being chipped away at. Or has he? Nine years ago, the "Pacman" upended the bigger Miguel Cotto for the WBC and the WBO welterweight titles after referee Kenny Bayless stepped in to halt hostilities when the Puerto Rican slugger could no longer answer the pummelling being administered to him by the then 30-year-old "Pound for Pound" king. The Cotto TKO came at the heels of Pacquiao's third-round decking of British sensation Ricky "The Hitman" Hatton in what many are calling "Manny's Greatest Hit." After the convincing victories over Hatton and Cotto, many aficionados declared that Pacquiao would be the most dominant boxer of his generation and most pundits, heading into his succeeding fights (against Ghana's Joshua Clottey, Mexican behemoth Antonio Margarito and iconic "Sugar" Shane Mosley), foresaw knockout wins for the General Santos native and that he would retire as one of the greatest ever. Not only did Pacquiao never win again by KO, but he also dropped four of his next thirteen bouts-more losses in nine years than in his first fourteen years as a professional. The power was somewhat still evident but he just could not finish them off as many have been accustomed to witnessing in the past. Age diminishes many things in a prize-fighter's skillset: speed, stamina, ability to absorb hits, recovery times, etc. Power is usually the last thing that goes, especially if that has been a trademark. George Foreman, in his prime, was said to have had the hardest hitting power of all heavyweights at the time, and that it took Muhammad Ali a lot of strategy changes-and the infamous African humidity-to finally deal Big George his first defeat in 41 professional bouts during the "Rumble in the Jungle" in 1974. However, Foreman-after initially retiring from boxing in 1977-came back to the ring in 1987 and along the way almost even unified the heavyweight division (including a Vegas-crashing tenth-round KO against erstwhile undefeated champion Michael Moorer in 1994). Foreman's power was still with him even into the twilight of his storied career even if he looked to be like an old man just trying to survive the quicker opponents' onslaughts. He still won 31 of his 34 bouts in his return to the sport and always owed his later success to his power when everything else faded away. Pacquiao is of a similar mold, but not exactly the same. The Clottey fight revealed many flaws in him that was later exploited by Timothy Bradley, Jr. in their first encounter in 2012. Clottey showed that by not engaging the favorable strengths of Pacquiao and adapting a clinching and covering up gameplan, Pacquiao was not as effective as when he went up against the likes of Marco Antonio Barrera, Erik Morales and even the aging Oscar de la Hoya; fighters who had to go toe to toe because their skillsets had them needing to. Clottey just defended against the big punches and engaged Pacquiao in a dance recital. Pacquiao could not floor the larger Margarito, but proceeded to rearrange his face. While against Mosley, the respect was clearly evident. When Pacquiao stepped on Juan Manuel Marquez's foot to end the sixth round in their fourth and final meeting in 2012 and paid for that accident by greeting Dinamita's right hand with his face, it changed the whole psychology of how to be aggressive in a more controlled manner as to avoid a similar fate in the future. Many notice how "balanced" Pacquiao's stance had become coming into the first Bradley tiff (where the young American upstart combined the Clottey strategy with a mix of Guillermo Rigondeaux's "tap and run" gameplan). The power punches were reserved for obviously open attacks and a premium on defense was also noticeable. Perhaps the judges saw as a sign of weakness. It was akin to a formerly brash poker player now resorting to "calling" rather than "re-raising" in the first sign of aggressive offense from a head-up opponent that is seemingly weaker. That player now relies on post-flop acumen rather than controlling the hand from the get-go, which might not turn out to be a good idea-in any sport. Pacquiao was now allegedly waiting for the man in front of him to make his move before coming up with a retaliation sometimes two or three sequences later. Needless to say, Bradley got away with a controversial points win and the result was debated for years. It marked the first Pacquiao loss since his unanimous decision defeat against Erik Morales in March 2005. Flashes of old glory were seen during eventual fights against Brandon Rios, the second Bradley matchup, and against up-and-coming Chris Algieri, but it became obvious that Pacquiao-although still a winner-had lost something after the losses to Marquez and Bradley the first time. Or was he in the process of reinventing himself? Were those three bouts real world experiments? When the much-anticipated encounter against fellow future Hall of Famer Floyd Mayweather, Jr. finally happened, "Money" resorted to an amplified Clottey-Rigondeaux-Bradley-Barney (the dinosaur) tactic that turned hugs and evasion into nods from the adjudicators for the undefeated American, brilliantly scouting that Pacquiao's fight mode was in transition. Had Mayweather agreed to the this fight in 2010 (when the proposals began), there is no doubt in anyone's mind that Pacquiao would have at least made it a lot closer and many will even say that Manny could have added another stoppage victory to his record; scalping one of the greatest fighters in the world. But that didn't happen and Mayweather picked the perfect time to agree to the fight-when he knew (with this version of his opponent and his carefully constructed strategy) that he only had a one in ten chance of losing, with the one (Manny's power) diffused with all the embracing and running.  Pacquiao's last fight against Australian Jeff Horn (in Australia) was the farce that really shouldn't have happened. The reigning champion (Pacquiao had just won the WBO intercontinental welterweight crown against Bradley and won the WBO welterweight title against Jessie Vargas) goes to the home country of the challenger and fails to finish off his younger foe leading to the judges to decide the outcome. It was supposed to be another "mandatory" defense that went awry. In that fight, everything discussed here was more glaring but yet there were signs that the experiment was beginning to bear fruit. Pacquiao displayed the poise of an evolved fighter-the circumstances were just not in his favor. The Pacquiao we see today is more patient, crafty and resilient. He still has the power and a lot of the speed from his younger days but is more cautious on when to mix it up. He's no longer the knockout artist that indirectly ended Morales' and Hatton's careers but now a veteran who still knows how to win but no longer needs to be flashy doing it. He now (again to use a poker term) "picks his spots" and being a dedicated student of the sport, now finds innovative ways to score-much like Dan Majerle graduated from being "Thunder Dan" (the dunking phenom) to one of the most feared shooters in the NBA during the 1990s. The camp of Lucas Mattheysse will be including in their to-do list the film-viewing of the Horn fight to see what the Australian did right to come up with an initial game plan against the 39-year-old Filipino. They could be setting themselves up. Margarito's camp studied the Cotto film and was completely surprised that Pacquiao came up with something else in the very first round to have them reeling and falling into a web of adjustments within the contest that was far too late. Bradley-after losing in the rematch-felt that he was up against a different fighter the second time around. If Horn and Pacquiao meet again, the Horn camp will have to be extremely lucky to get away with the same strategy. Chances are, they may consider hugging and running at one point. Matthysse will have to realize that Pacquiao is no longer the same fighter that he was when he was toiling in the featherweight and lightweight divisions. He has evolved into a better specimen that will grind in the squaring circle no matter how long and arduous it may have to take to get the win. He (among other things) will have to find ways to make it "ugly." The Argentine's KO wins against Emmanuel Taylor and formerly unblemished Tewa Kiram could bolster his confidence against his older challenger, but once the bell sounds in Kuala Lumpur this July, which Manny Pacquiao will he be facing: the new-look grizzled, patient stylist or a faster, smaller and younger version of George Foreman? We'll all find out in a few weeks.

|